Ali Cha'aban: An Interview Uncovering the Layers of his Work

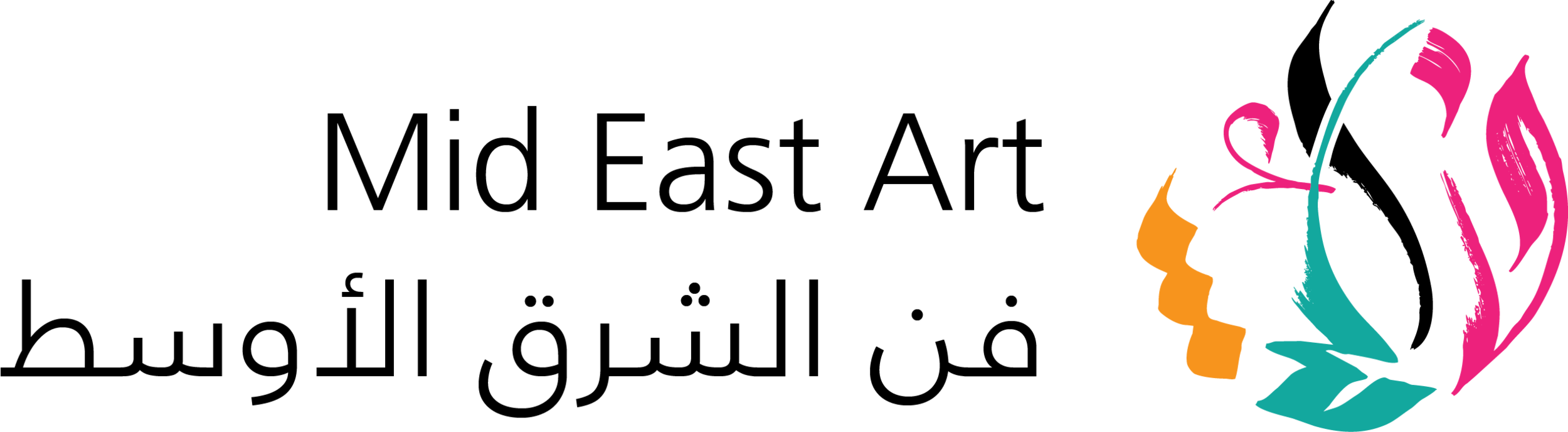

Ali Cha’aban in front of “The Broken Dream”, silkscreen on Persian carpet, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.

Ali Cha’aban. Image courtesy of the artist.

Meet Ali Cha’aban, a Lebanese born, Jeddah based artist who is tackling what it means to be Arab in today’s world. Ali is part of the 1980s/90s generation caught between notions of cultivating the Arab identity, and belonging and estrangement. Artists within this generation are reflecting on these memories that constantly loop through their everyday conversations with friends and families, a sort of permanent nostalgia and cultural reverie of a glorified past.

As Ali reflects on this complex - “The key benefit of our Arabic nationality, is that we are strangers everywhere. Even strangers in our own home.”

Ali’s works are triggering new debates relevant to global politics and social realities, explored through his interactive installations, street and fashion photography; he even has produced his own inspired unique clothing pieces. His multidisciplinary and conceptual work is part of a growing collective of contemporaries that include Khalid Zahid, Sarah Al Abdali, Rashed Al Shashai and Arwa Al Neami, along with the blogger ‘The Confused Arab’’, among others.

The artist’s works range from clever titles that include “The Broken Dream II” or “My Imagination is no Longer Enough to Complete my Journey” and “What’s halal my killer? What’s haram my dealer?” Comic strip scenes of bruised superheroes are superimposed onto Persian rugs; kitschy titles are derived from famous rap lyrics and portraits of friends are lit with uncomfortable lighting. Ali is also an emerging fashion photographer, shooting for Vogue Arabia and Fashion Prize winners’ collections, even working on a campaign for Nike in 2017 during their Satellite Culture campaign.

This is not the first time we see pop art and cross cultural references across artists’ works.

Along with Ali, a group of Arab artists today are mixing both Eastern and Western imagery, reflecting this sort of in between-ness found growing up, being educated or learning cross-culturally in the clothes that they wore, the architecture of their homes and cities and the television shows and movies they grew up watching.

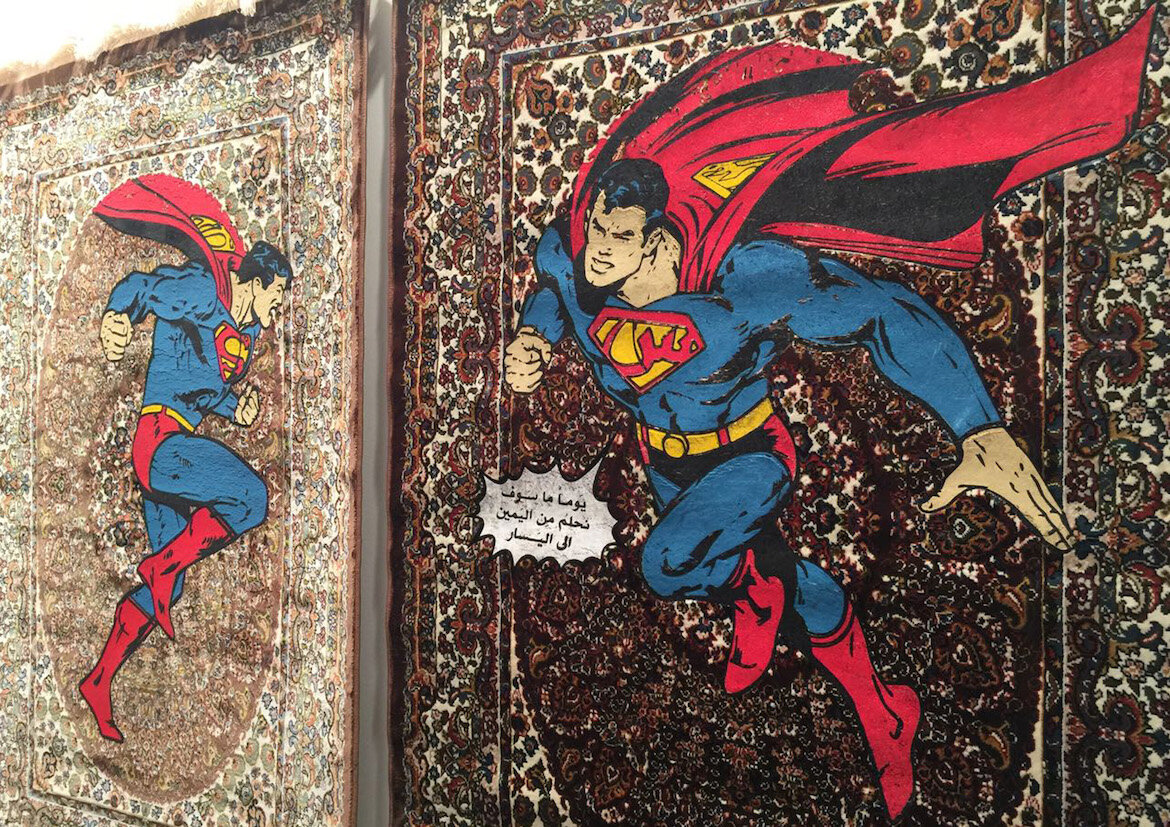

Saudi artist Shaweesh displays Captain America alongside refugees during the evacuation of Fallujah in 1949. Palestinian, Saudi based artist Ayman Yossri Daydban’s tissue boxes display Middle Eastern movie posters from the 1940s to 70s. The late Chant Avedissian depicts icons of Egyptian history, such as notably Umm Kalthoum, Farid Al Atrash and Abdel Halim Hafez.

These are just but a few who are representing imagery depicting the region and country at the height of its cosmopolitism and a shared sense of notion of childhoods across cultures. Artists are telling us: we are weeping, but we are also laughing out of happy times. We are feeling confused and alone with a clash of identities. But we are also collaborating on how to reconstruct these sentiments and recreate a future incorporating a culturally rich past into today.

Ali’s works are visually powerful, drawing the viewer by their neon lightings, easily recognizable characters and familiar technicolor hues. Heavy with the iconography of Arab culture, they have a message that cannot be hidden beneath one’s living room curtains in a home. They instead act as centrepoint to encourage discussion and debate on harder socio-political issues.

Ali Cha’aban, 12pm class, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

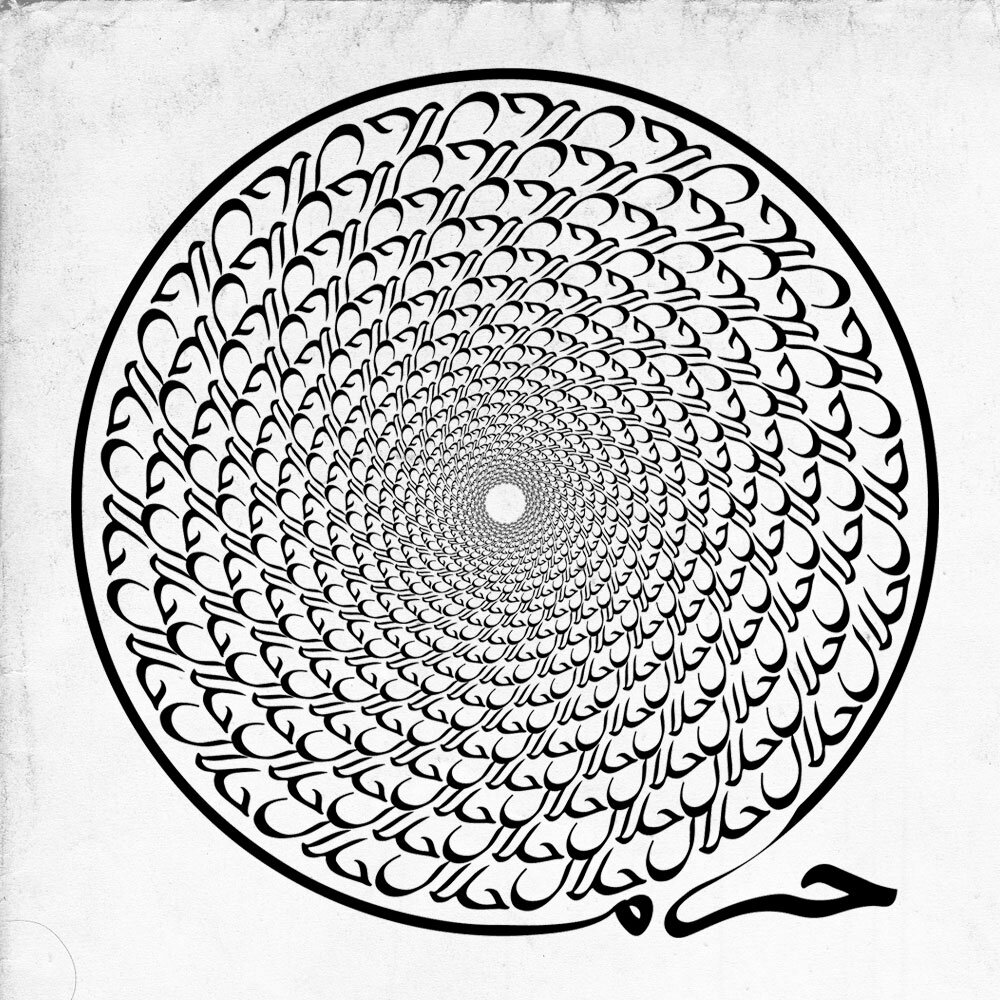

Ali Cha’aban, The Holy Decibel, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

The first time I noticed Ali’s work was during Sharjah’s most recent Islamic Arts Festival held in the Sharjah Art Museum. An immersive installation titled ‘The Holy Decibel’ was composed of a wooden dome in the shape of a mosque with speakers pulsating a heart beat. Comforting and meditative of a space, the work was a powerful rendition of the Quran’s ability to lower blood pressure and sooth the heart beat. A few months later, I found a neatly folded Persian carpet in the shape of a classroom paper plane titled ‘12pm class’ on the floor of Manarat Al Saadiyat’s Gallery’s Week at Hafez Gallery’s booth. Ali’s Persian rugs, an staple home piece to any Middle Eastern family’s home, also hang on the wall with images of Stan Lee characters; look closer and find that Superman and Superwoman are bruised; a clash of cultures is happening and the identity crisis recounts a younger Ali and others infatuated with Western ideals but growing up now proud of their Arab identity.

Mid East Art had the chance to speak with Ali on his inspirations and what he’s excited about.

MEA: What are some of your earliest childhood memories?

AC: The sad truth most of my childhood memory are revolving around war.

My earliest was in the 90’s where were trying to leave Kuwait during the Iraqi invasion, then moving to Lebanon where the Israeli invasion was still occurring around our village in the South. So my childhood memories are torn between the sensibilities of creating good moments that are disturbed by the sounds of alarms and collisions.

MEA: What do you miss the most of the childhood you had?

AC: I do miss the sense of community we had, because as kids in a village, we shared an unwritten law: to imagine. We used to imagine scenarios and play it out as kids, whether on our bicycles in the afternoon, or the football games that were interrupted by our parents screaming that dinner is ready; or even when the electricity shuts down and we all rush to ignite the candles. We would watch TV shows on a noise-heavy TV that was powered by a small generator that would cut off if you light even one light-bulb extra. This is where the love for western visuals came, because these visuals meant “safety.”

MEA: In an earlier interview you mentioned you wanted to start your very own advertising agency catered to small businesses. Does this still ring true? How has your earlier vision changed since you wanted to be in the creative industry?

AC: Oh that vision changed drastically.

At first I used to be a kid that was enslaved in agencies trying to find a calling.

Now I can’t do commercial work; I find it bad for my soul. Everything I do now has to have a story, a meaning, a final message that eludes to a narrative whether in my fine arts practice or my creative work with clients such as Nike, Vice, Selfridges, Gucci; it always started with a concept and an issue that I wanted to tackle; that issue is regularly my identity.

So no, now I like to have an agency that focuses on cultural and creative content. Focusing on creating campaigns as projects, that are inspired by cultural traditions, allegories, folklores and to always be politically correct. To avoid messes like D&G in Asia.

MEA: What is your perspective on local fashion, design, arts collectives today in the Gulf? Since when did this pick up (what years did you start to notice it) and which cities were some of the first to begin?

AC: The contemporary art scene has raised the bar for emerging artists and designers to create tributes to their culture with an evolving state of mind. I always say that I’m super-proud of my generation. Young Arabs have been creating and producing things that have seriously put us on the map. We have been able to forge an identity for ourselves and an ever-growing aesthetic that defines us. The Arab art scene is slowly generating it’s own notion of the Arabic Renaissance, paving a visual identity that will be discoursed in decades to come both academically and historically.

I saw it pick up initially in Dubai and Saudi Arabia around the early 2010’s with initiatives such as Art Dubai (Emirates) and 2139 (Jeddah) and Edge Of Arabia (Saudi Arabia) that really put the Arabic on the Map.

MEA: What is Live Demo Collective?

AC: A collective that never saw the light of day, because it disregarded the concept of “collective,” I believe it's because sometimes in one’s nature to be selfish. This was my first experience to work with other artists as one, it was a bad experience since I saw how bad sometimes people want the glory and the casualties are their friends. So I focused on myself and I only collaborate with people that want the same thing I want.

MEA: How has different generations reacted to your work? That are Arab? Or Non-arab?

AC: Let’s face it, the idea of freedom of expression in the entire world does not come without repercussions. So understanding that philosophy will help you develop your work with more confidence, if you’re confident in what you convey then the critical response won’t affect you. As an artist in the Middle-East I was able to develop a thicker and tougher skin, because I endured much criticism without being phased, especially when we have multi-layered cultures that don’t necessary agree with your way of thinking. My work has been called “depressing” on multiple occasions; but that didn’t stop me from always talking about the nostalgic Arabic identity.

As a contemporary artists, I consider myself from the school of Marcel Duchamp, an art that serves the mind. Once we depart with the ideals that art should be aesthetically pleasing, we find ourselves in a place where the idea, concept or message is more important than the execution. It differs from one artist to another, I for one believe the message is more important than the appearance. I work to provoke a thought or an emotion; to create a discussion and generally it is achieved by disconnecting from the visual beauty.

MEA: How has social media impacted your work?

AC: Connectivity. You connect on a larger scale, multifaceted observers with their own connotations of your work. Which in return helps me mature my message, refine it and cultivate it for a larger mass to identify with my work.

MEA: Are you continuing to explore this metaphysics in Islam project with Khalid Zahid? What have you uncovered from this?

AC: It’s a never-ending research, and yes of course every time Khalid and I link up we discuss new concepts that relate to that field. We even have two concepts ready for production, one that will be submitted to the Sharjah Calligraphy Biennale.

Duality was uncovered. One thing that was established from the creation of the work is ‘Duality’, our Islam functions heavily on the ideology fo duality. The existence of opposites is very crucial in our religious and spiritual upbringing. Going back to the very famous question of “Path or Choice”.مسألة†العبد†مسير†أم†مخير Everything functions in dualism, heaven and hell, sadness and happiness, good and evil etc. The artworks explore the same ideology where the Dome questions the more important organ the heart or the brain for spiritual connection, the heart “al-Fouad” being mentioned more in the Quran than the brain. The Mihrab also questions existence in duality, being eternity and the cessation of being. Even Allah’s names are divided into Masculine “Strict” adverbs and Feminine “Softer” adverbs, like “Al Rahman” and “Al Rahim”, as well as “Al Jabbar” and “Al Bari.” Leading us into the heaven’s which in return omits that duality.

From my research we’ve also realized architecture plays a visual and physical role on our spritual upbringing the Dome for instance, which allocates sound. Sound was the keyword, reframing the multiplicity of sound led us to investigating the connection OF sound; the emotions that strike a spiritually engaged person when they hear or listen to the Quran.

MEA: Are you more comfortable with the camera or producing large installations?

AC: I really can’t tell, both of them have different emotions that go through me. I deal with identity crisis through my work, I deal with it through my profession as well, where the latter focuses more on aesthetical relativity. In art direction I try my best to depict a scene or a story in my visuals, I still believe photography is the best form of capturing a moment, but I still deal with my ‘scenes’ as an artwork. I believe I become a renaissance man contradicting my earlier school of thought. But I learned to disconnect and sometimes connect both schools when approaching every project.

MEA: What works are you working on now that you would like to share with us?

AC: Usually in winter is where I conceptualize my ideas for the next year both commercially and in the fine arts.

So right now, nothing has materialized yet. But there might be a project I’m working on for Art Basel Miami called “Light & Stone” with a fellow artist Jason Seife; waiting for approvals and if we have time.

MEA: What is an unrealized project you would like to create?

AC: A project about the West Bank Barrier.