Hope is Contagious in Prison: Inji Efflatoun in Isolation between 1959-1963, Egypt

Welcome to ‘The Quarantine Files’ series —where we chronicle the hours, days, weeks and eventually months of our time incubating indoors and channeling our short bursts of creativity. As hungry as we’ve become for nature-filled walks with greenery and endless ocean waves (as I type from my apartment views of a concrete jungle in Dubai), we’re adapting to alternative modes of intellectual and social nutrition and embracing our inner poet, journalist, cinephile and painter-self within our four walls. It’s been an overwhelming sensation to face the fact that we will survive these next moments, however long they last, indefinitely, indoors and in my case, in silence, save for the chitter-chatter of my thoughts ricocheting within me. The clock ticks (rather the digital nanoseconds click), the mornings, however long or short they become now, turn to night either too quickly or begrudgingly slow.

Firstly, my prayers go out to those and their loved ones who actually have serious medical conditions at this moment. Fortunately I have not been faced with this situation, but am sending my utmost regards to the creative community and extended families at this difficult time.

Inji Efflatoun in her studio in Hassan Sabry St., Zamalek, Cairo, Egypt, Courtesy Safarkhan Art Gallery.

While we sulk in our seventh season of our favorite Netflix series, I wanted to share an enlightening story on a pioneer Egyptian artist who will turn our trivial complaints into plain bonafide excuses. The story of the Egyptian modern artist Inji Efflatoun (1924-1989) is one of bravery, perseverance and ingenuity—sprinkled with humor and wit. Inji was in every sense a rebel noted equally as a women’s rights activist (even going undercover at one point as a peasant) as she was a talented painter rising to fame in the midst of World War II—all while keeping herself fashionably dressed and coiffed! Her works were daring in subject matter, showcasing the plight of Egyptian workers that included the peasants, the craftsmen and the laborers depicted in miserable conditions, while also focusing specifically on women and their daily struggle.

Inji’s self-isolation experience was dealt not by a massive epidemic like we find ourselves today, but in her incarceration in Egypt from 1959-1963.

That’s over 4 years of dealing with quarantine in prison life - but she lived to tell the story, keeping artistically stimulated amidst the isolating circumstances, and attributing this time to her greater self-discoveries— as illustrated very vividly with biting humor in her post-mortem memoir (and quoted from the artist in beautiful detail in the last few paragraphs of this post). Finding the extraordinary in the most mundane and trivial surroundings in her jail cell, Inji captured the sheer tragic yet poignant moments behind prison bars - whether it was in painting an inmate and learning her telling story, or finding the simple and beautiful nature through the small windows or atop the prison’s roof overlooking the Nile river. As she noted “Prison was a very enriching experience for my development as a human being and artist. When a crisis or tragedy occurs, one can become more strong, or be destroyed. I became more open to people, to life. Before I didn’t compromise. Now if I see someone’s weakness, I accept it’” (1).

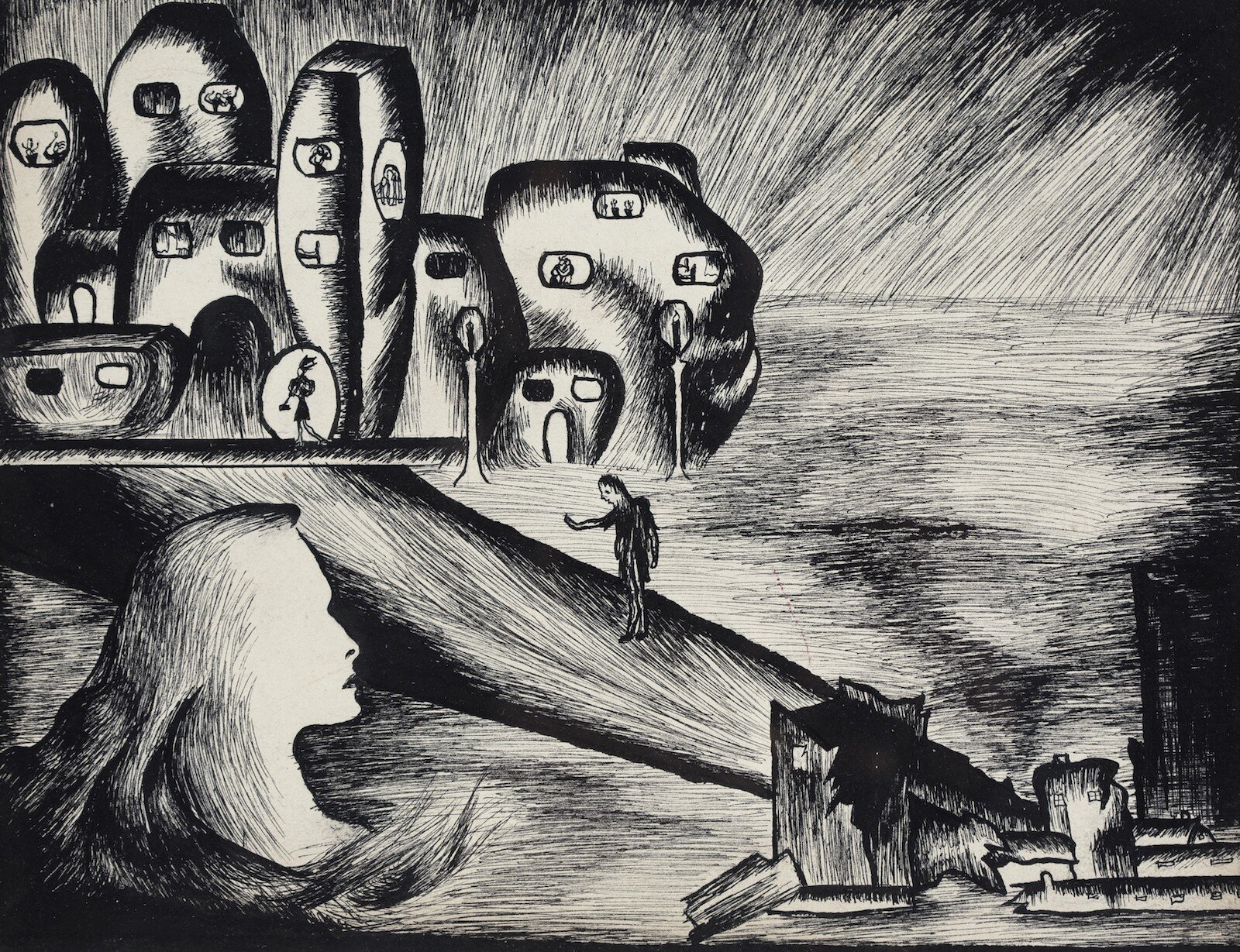

Inji Efflatoun, Expectation, c. 1940s, Ink on paper, 12 x 21 cm. Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.

As the amazing story of Inji unfolds in my below post, let’s take a visual snapshot of her confinement while we are in self-isolation too; instead she was cramped for four years in a depressing overcrowded ward amidst a group of anxious and depressed women. Despite these miserable conditions and fears, Inji maintained a sense of hope and logic: she improved in her artistic style, cultivated a sense of camaraderie with her fellow inmates, and even developed a pseudo art business smuggling her paintings out of the prison— thereby keeping a small but central link to the outside artistic world. Hope is contagious, and she illustrated this sentiment so beautifully in her paintings while experiencing this innate sensation in the prison cell with the inmates and guardians.

Inji was as unstoppable in the political arena as she was on the canvas.

Her work in both spheres has left a lasting impact on generations of artists and Egyptian feminists and social activists; and as articulated in her manifestos along with her depictions that honor the everyday humble Egyptians and beautiful rural landscapes. As a woman artist practicing in the mid 1900s, her talents solidified a strong female artistic movement along with other female painters practicing during this time. Many of these women used their art to raise political and social consciousness in the wake of the country developing a national identity. Key artists include Gazbia Sirry (b. 1925), Zeinab Abd El Hamid (1919-2002), Effat Naghi (1905-1994), Marguerite Nakhla (1908-1977) and Margo Veillon (1907-2003), among others.

Inji Efflatoun. Image courtesy of Art Talks, Egypt.

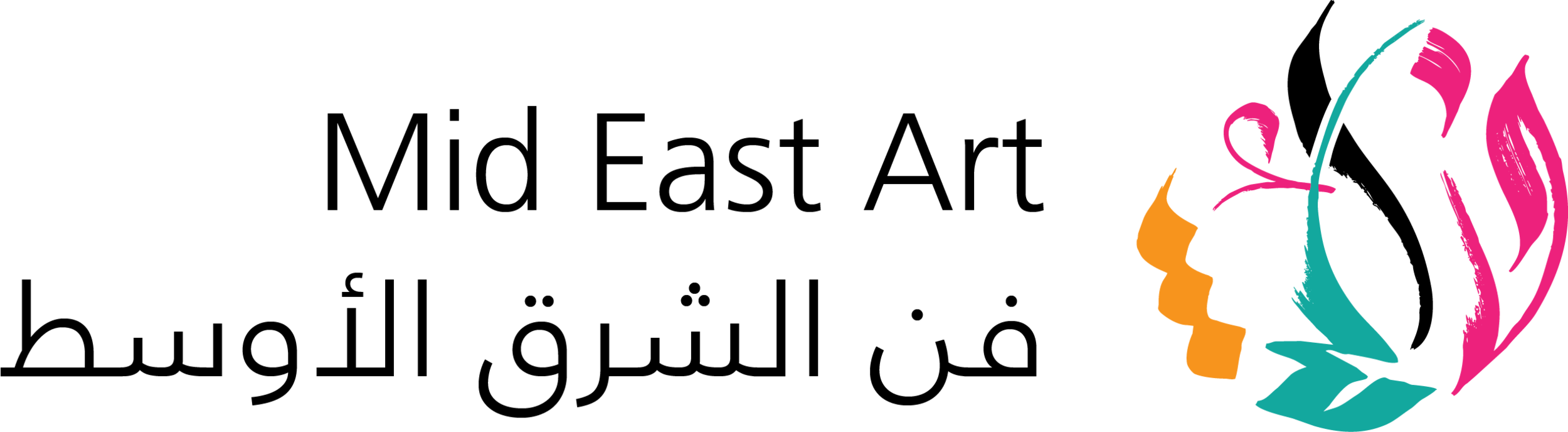

Inji Efflatoun, Portrait of a Prisoner, c. 1960, oil on canvas, 29 x 41 cm, Courtesy Safarkhan Art Gallery.

As Sultan Al Qassemi shares with Mid East Art “Through her activism, her manifesto, her paintings and her writings, Ini Efflatoun represented the poor, the forgotten and the downtrodden. Even decades later it is rare to come by an artist who has depicted topics as varied as female prisoners, Palestinian freedom fighters and working class laborers with such depth and humanity.”

Inji was, as surrealist Egyptian writer George Henein beautifully puts - ‘Setting up her imaginary world around a bird of dreams and the heavy weight of the void.’

Born into a liberal upper class francophone family in Cairo, she received art classes at 14 years old from the esteemed Kamel El-Telmissany (1915-1972), noted as an active artist, critic, poet, political activist and filmmaker. (Interestingly enough, on the account that one of the most famous modern Egyptian painters Mahmoud Saïd (1897-1964) saw Inji’s early illustrations produced for her older sister Gulperie (known as Boulie) and he urged her mother for Inji to receive lessons!).

It was just a few years earlier that El-Telmissany signed the ‘Long Live Degenerate Art’ manifesto in 1938 and then became the co-founder of the leftist Communist and anti-imperialist ‘Art & Liberty’ surrealist collective in 1939 that lasted until 1945. (to see a major exhibition on Egyptian Surrealism that just took place in 5 major museums in Europe from 2016-2018).

Art and Liberty, 1941. Front row, left to right: Jean Moscatelli, Kamel el Telmissany, Angelo de Riz, Ramses Younan, Fouad Kamel. Back row, left to right: Albert Cossery, unidentified, Georges Henein, Maurice Fahmy, Raoul Curiel. Image courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Egyptian Surrealism emerged in the late 1930s in opposition to the rise of fascism and nationalism in Europe, against British colonial rule and Cairo’s conservative artistic scene. Key artists of this group include Ramses Younan (1913-1966), Fouad Kamel (1919-1973) and Georges Henein (1914-1973) who produced work with a ‘shock value’ that emphasized the harsh realities of the time. These artists found themselves within a time wrought with war and terror brought upon by totalitarian regimes, after World War II raged through Europe, along with an intensifying militant nationalism existed within Egypt. It was also during a time artistically when artists debated how currents of European Surrealism were to be incorporated within the stylistic and conceptual local Cairo art scene.

Rateb Seddik, ‘Liliane Brook et son orchestre aveugle,’ ca. 1940. Image courtesy of Musee Rateb Seddik Le Caire.

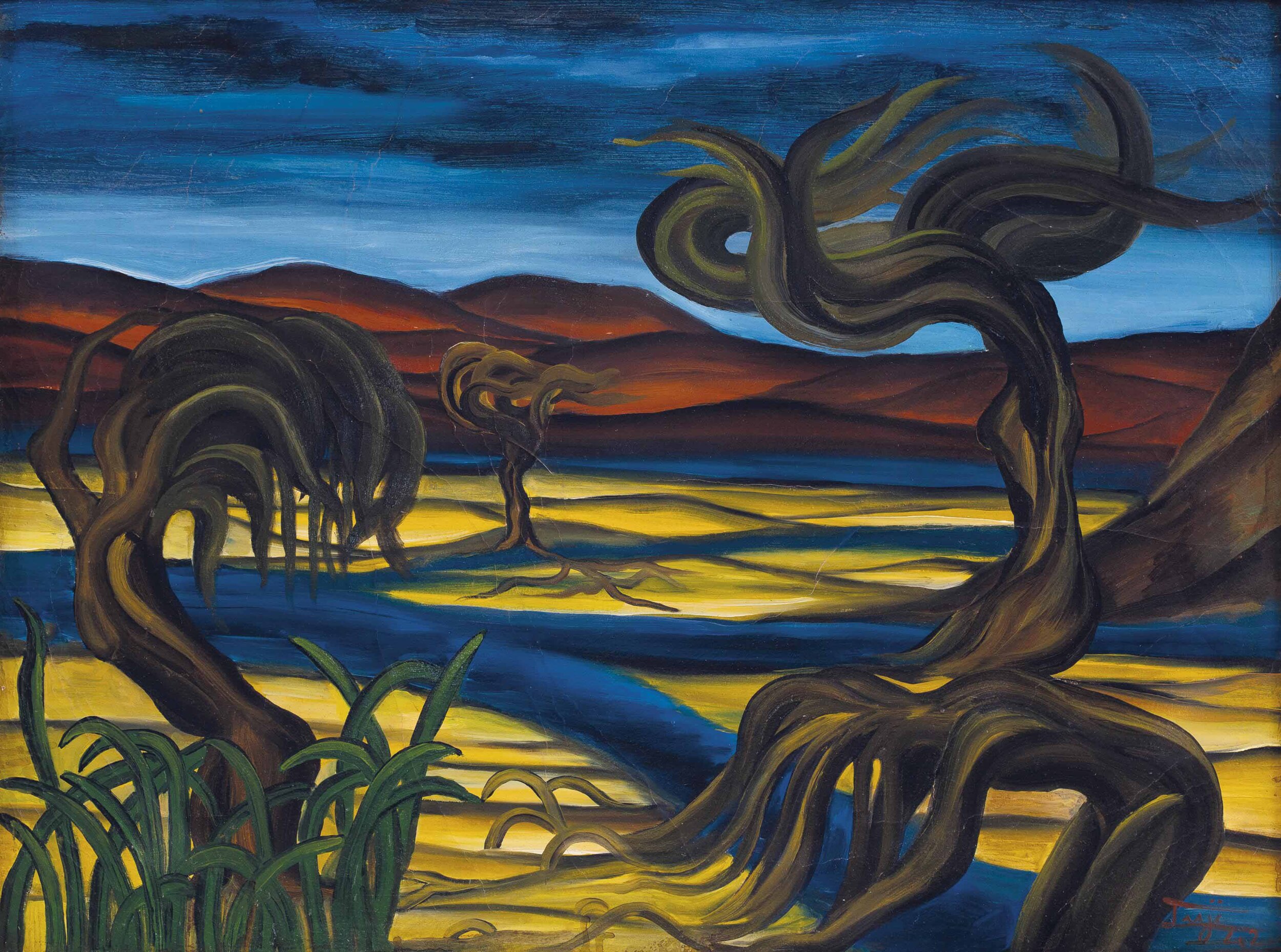

At an early age, Inji found herself within this avant-garde artistic leftist circle of dynamic and outspoken artists and intellectuals. In 1942 at the meagre age of 18, Inji took part in the third ‘Art & Liberty’ exhibition (there was only 5 shows ever) and was the youngest amongst the 24 exhibitors. Her surrealist works often depicted atypical compositions of a young suffering girl trying to escape and discover herself, liberating from the social, patriarchal and colonial burdens of the time. Notable works of this time include ‘Young Girl and Monster’ which depicts a frightened girl running while being chased by a vulture along with trees that symbolized as she states ‘people who were suffering, and representing dreams and spirits.’ (2) Inji would eventually become one of the first women to study in the art department of the University of Cairo in 1945. She then studied one year under the Swiss artist Margo Veillon and later with the studio painter Hamed Abdallah (1917-1985). It was during this time she began to make many trips to ancient towns such as Luxor and the rural areas of Nubia, painting the men and women at work. So much was she enthralled with the Egyptian society, she refused her mother’s request to finish her fine art studies in Paris stating ‘It was very tempting to go to a good academy, but I refused completely. With five or ten years of Parisian study I would be a better artist, but I would know nothing of my country, and then it would be too late. Now I began to understand my roots, to be Egyptianized.’ (3)

Inji Efflatoun, Ezba (Farm), 1953, Oil on board, 47 x 63 cm. Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation.

In the political arena, she published several poplar manifestos with a group of women to support women’s rights and peace, and became one of the founding members of the League of University and Institutes’ Young Women along with actively participating in the Women’s Committee for Popular Resistance. She published numerous political pamphlets, such as Eighty Million Women With Us (1948) and We Egyptian Women (1949). After she met intellectual and feminist Sayza Nabarawi in 1950, Efflatoun joined the Youth Committee of the Egyptian Feminist Union.

Inji Efflatoun, Portrait of a Fellaha, c. 1960, oil on canvas, 50 x 70 cm, Courtesy Safarkhan Art Gallery.

While her work grew politically, her paintings in parallel became more politically engaged. Works garnered titles such as You are Divorced (1952), The Fourth Wife, and We Will Not Forget (1951). In 1956 the artist met Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974) when he visited Egypt and his social realist work had a tremendous impact on her own.

In 1959 she went undercover disguised as a peasant under the Gamal Abdel Nasser regime as the communist party and Egyptian socialist movement was being outlawed. In March of that year she was secretly arrested under Nasser along with 25 female political activities. She was imprisoned for 4½ years between June 1959 and July 1964. It was here she witnessed the harsh realities of prison life - of women behind bars in filthy cells undergoing horrific treatment, each in their own way representing and subject to their own social tragedy. Despite the conditions, Inji was eager to continue painting, going at lengths to secure permission to paint amidst strict censorship enforcement that was eventually lifted. She initially received permission to sell her paintings outside the jail, with proceeds to benefit the prison, however was unsuccessful as no one wanted to buy the depressing compositions outside the prison. Ultimately she received authorization to paint with the help of her sister Boulie (who also would be imprisoned) and ultimately smuggled her precious works outside and shared them with other artists for critique by those such as Tahia Halim, Angelo de Riz (Italian, b. 1900s), among others.

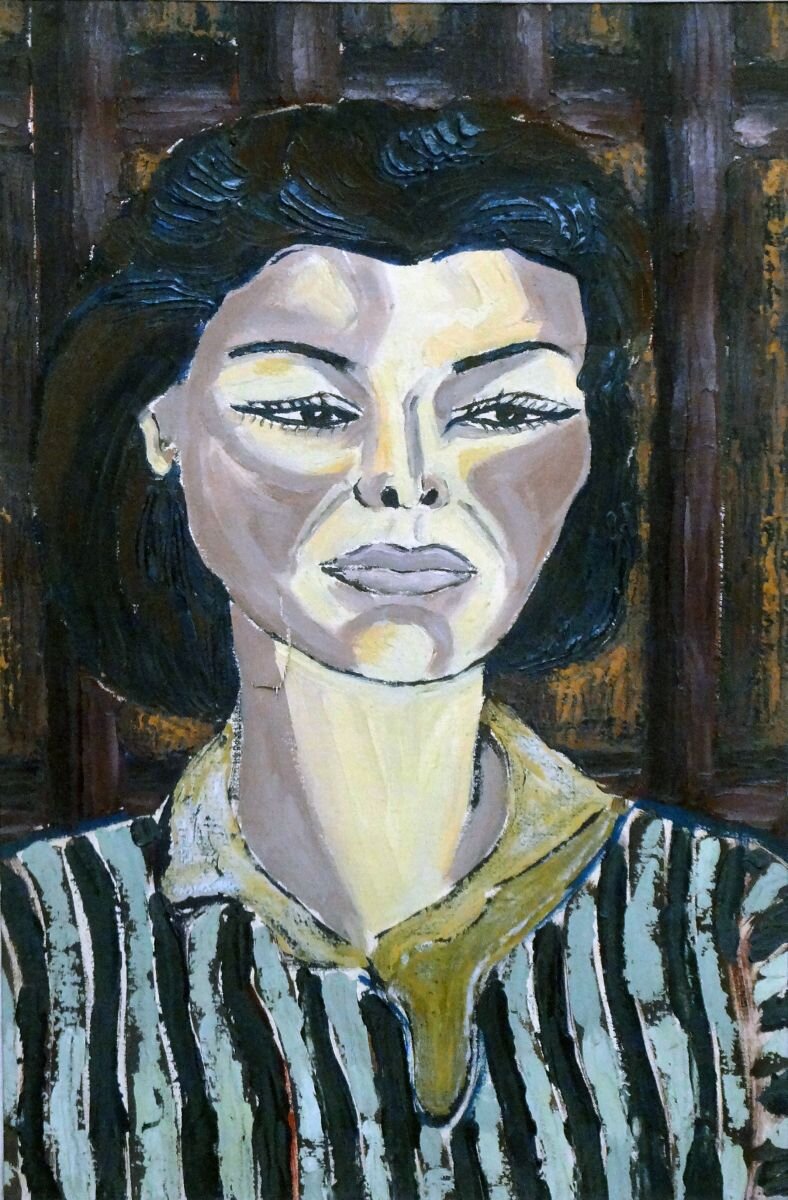

Inji Efflatoun, In the Woman’s Prison, c. 1960, Oil on wood, 58x52 cm, Courtesy of a private collection.

Following her release from the prison in 1963 the artist painted subjects that evoked a sense of freedom, in her optimistic depictions of trees and sailboats and as illustrated in her brighter, highly textured compositions. It seems her confinement had a serious impact on seeing the light..

The below are a few excerpts from her posthumous memoirs that describe her time in the prison:

‘Some two or three months after I arrived in prison [in 1959], I felt a desire to paint and with it came a refusal to surrender to the status quo…I would go up to the roof of the building to paint anything I could find, eventually painting the inmates…

One of the most important subjects I painted from inside the prison was Inshirah, who had been sentenced to death, but her execution had been postponed for one year until her child was weaned. Those sentenced to be executed were placed in a cell under special guard so they wouldn’t commit suicide, and they wore red uniforms. While awaiting Inshirah’s execution, I felt the massive tragedy of her story, as she had killed and stolen under the pressure of extremely harsh conditions and overwhelming misery. When I asked to paint her, the director [of the prison] told me that it would be very depressing. I did indeed paint her and her son - this was one of the paintings that were confiscated by the Criminal Investigations Department…

Inji Efflatoun, ‘Country Sheikh,’ c. 1950s, oil on panel, 70 x 45cm., Image courtesy of Mathaf, Museum of Modern Art, Doha.

Inji Efflatoun, 'Motherhood,' c. 1950s oil on wood, 75 x 47 cm. Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah

After some time I lost the desire to paint the prison and its inmates — the whole place disgusted me. I began to paint what nature there was behind bars, as we did have some gardens, trees and flowers. I was fascinated by a tree that was near the barbed wire - I’d paint it in every season, and such meticulous attention to a single object taught me a lot. If I’d be outside the prison I never would have painted just that one tree. My fellow inmates even named the tree after me; they called it ‘Inji’s tree.’…

‘There was a small tributary of the Nile where sailboats would pass by. We would watch from inside the prison as the sails caught the wind and men climbed up the masts to tie them down. Seeing the wind in the sails stirred many sorrows in me, and sparked an uncontrollable desire for freedom.. I obtained permission from the General Manager to go up to the roof of the warehouse..[and] when the boats appeared [the other inmates] cried out ‘The boats are here!’ I painted many pictures of sailboats, depicting our immobility agains the movement of the sails…

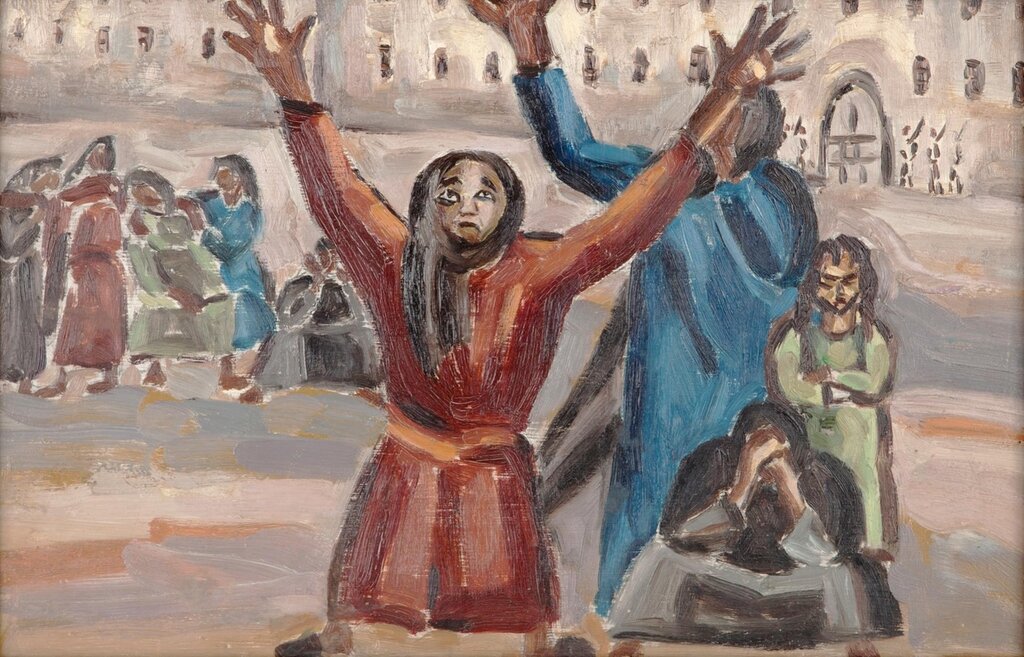

Inji Efflatoun, ‘Portrait of a Prisoner’ 1960. Artwork shown at Art Talks 2013 exhibition ‘Long Live Free Art in 2013, Cairo. Image courtesy of Art Talks, Cairo.

How to smuggle the paintings out of the prison? I’d wait until a painting had dried, then I’d remove the canvas from the wooden stretcher and give it to one of the wardens who would wrap it around her body under her clothes. I was worried they’d discover how we were smuggling them out, as this could result in my being completely banned from painting - a right that I had won only by a miracle. There was one warden who was particularly good at smuggling: we called her ‘the express train.’ She would deliver the paintings to my sister in return for a sum of money. Some of the doctors also helped me because they were not subject to inspection..

One of the most important subjects I painted from inside the prison was Inshirah, who had been sentenced to death, but her execution had been postponed for one year until her child was weaned. Those sentenced to be executed were placed in a cell under special guard so they wouldn’t commit suicide, and they wore red uniforms. While awaiting Inshirah’s execution, I felt the massive tragedy of her story, as she had killed and stolen under the pressure of extremely harsh conditions and overwhelming misery. When I asked to paint her, the director [of the prison] told me that it would be very depressing. I did indeed paint her and her son - this was one of the paintings that were confiscated by the Criminal Investigations Department… (4)

Footnotes:

LaDuke, Betty. “Egyptian Painter Inji Efflatoun: The Merging of Art, Feminism, and Politics.” NWSA Journal, vol. 1, no. 3, 1989, pp. 474–485. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4315927. Accessed 4 Apr. 2020. (quote pp. 479 & 483)

ibid. (quotes pp. 477)

ibid. (quote pp. 478)

Excerpts taken ‘From the memories of Inji Aflatun (excerpt); rear. In Sa’id Khayyal, ed. Mudhakkirat Inji Aflatun (Kuwait: Dar Su’ad al-Sabah, 1993). 236-44. Translated from Arabic by Sarah Dorman.