During Abu Dhabi Art fair this past November, I had arranged to meet with artist Khalil Abdul Wahid during a portfolio review he was giving to younger students, as part of Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation. I turned out to be part of a group of younger students and alum surrounding Khalil, eager to hear his advice on their works and practice. In what appeared to just be a discussion about their works turned out to be a larger conversation about the history of the UAE art scene. Naturally, Khalil spoke to these students about how he was taught by his teacher, Hassan Sharif, and I noticed how reassuring and exciting this was for them.

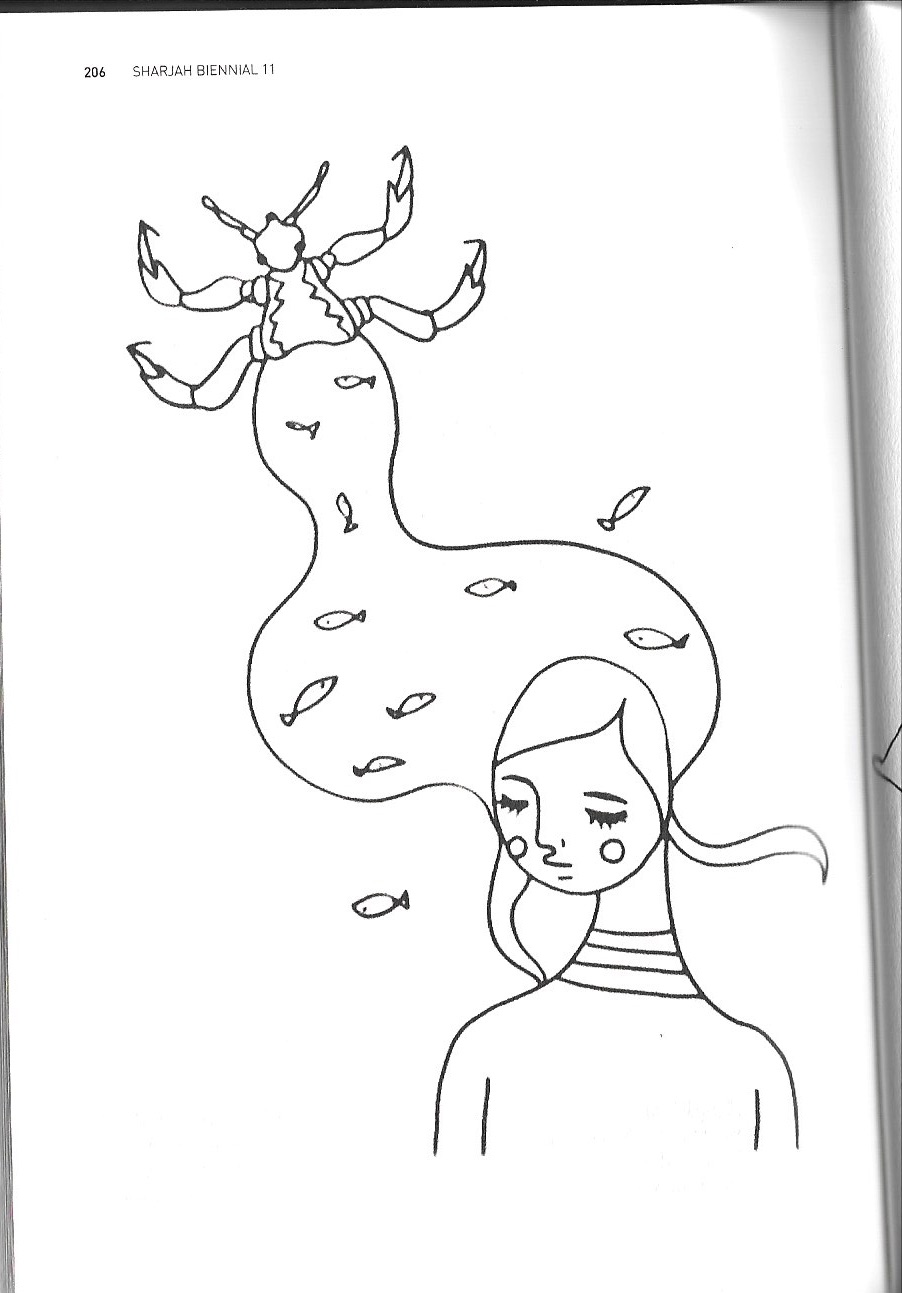

Taqwa. Courtesy of the artist.

One of these students turned out to be Taqwa Alnaqbi. A fresh graduate from the University of Sharjah's College of Fine Arts, she narrated the story of how she made her grandmother, who is unable to read or write, draw for her as part of her senior project. Of what I noticed of this match between Khalil and Taqwa was this sense of comfort for her to speak with someone from her own culture and excitement for Khalil to hear her enthusiasm to advance her practice and learn more about UAE art history. Devoting some time during university to try and fill in these puzzle pieces, she was now able to listen to someone analyze and critique her work by using older Emirati artwork examples.

This encounter turned into a friendship between Taqwa and myself, which involved a few bus trips to Khorfakkan and back, (I missed the last bus to Dubai one time) and a combined interview session with Mohammed Ibrahim. Taqwa's vision is in line with these older artists, in that she uses materials from her environment and understands the importance of listening to her elders, both at home and in her local art community. A native of Khorfakkan and an artist since a young age, she has now developed a passion for bookbinding and printmaking that uses the stories and materials that are close to her.

MEA: What is Khorfakkan to you?

Taqwa: All of my memories that I have growing up are from here. Because it’s a very small hometown and everyone knows each other, it’s really special. Khorfakkan is symbolized by nature, both in the sea and the mountains. It’s home to me.

MEA: What were your earliest memories there?

Childhood photos. Image courtesy of Suzy Sikorski

Taqwa: I was in first grade and my teacher gave us homework to draw something. I had no idea how to draw, I really was bad. I didn’t even tell my mom, but I went to my sister and I told her to draw something for me. I showed it to my teacher and she told me I was going to an art competition. I was terrified because I didn’t even make it! So I started to copy and copy that drawing. I actually found this drawing two years ago, and I realized it was the first drawing that I made, but really it was my sister’s..

MEA: So you can consider your sister was your first art teacher?!

Taqwa: Exactly. She’s a fashion designer now.

MEA: Was the Khorfakkan Art Center a big part of your childhood?

Taqwa: Yes my mom was really pushing all of my siblings to go there and to practice paintings and handicraft. She pushed us to make sure we have a hobby. We would stitch, do collage, draw and use clay. We didn’t do a lot of photography when I was young. I was much more interested in craft making because I loved using my hands.

MEA: It seems you come from a creative family. Someone is in art, one’s in fashion.

Taqwa: Yes I know. My late grandfather on my mother’s side was actually a designer who stitched wedding dresses. He used to make simple tools for daily use and sell them to neighbors. I don’t remember the tools but my mom used to tell me about that.

MEA: I bet everyone probably knew your grandfather because it was such a small town. In a way that’s what makes Khorfakkan so special.

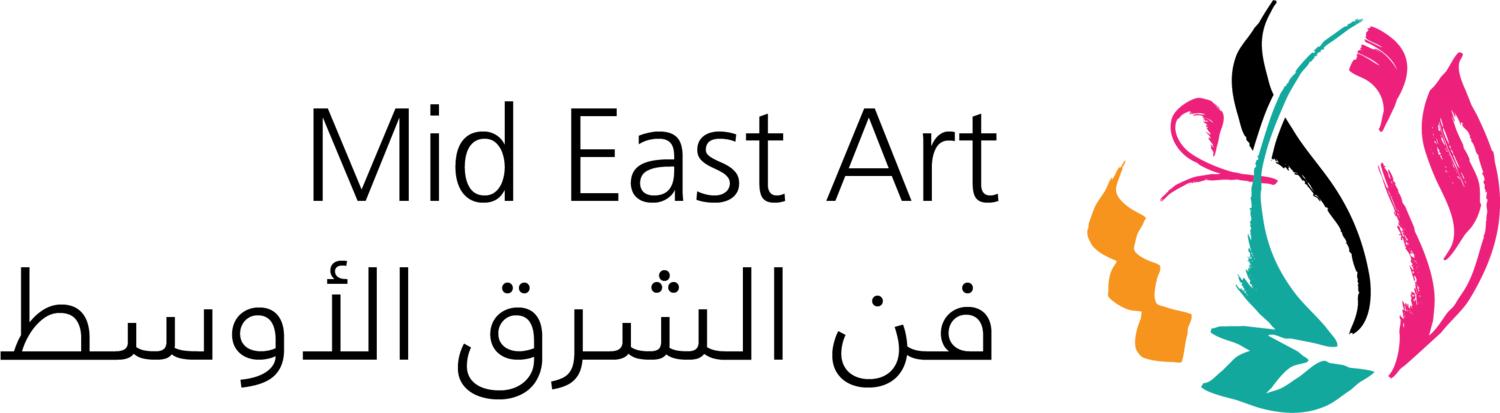

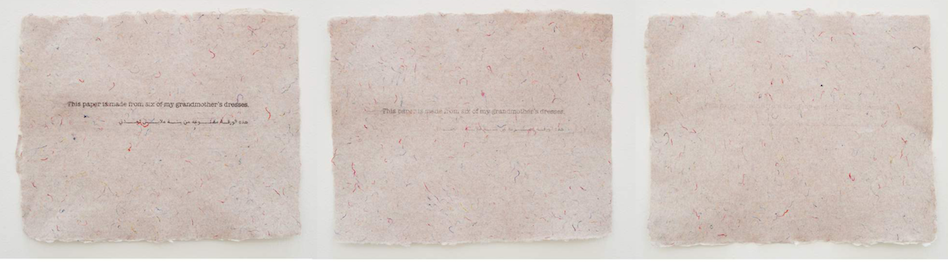

My Grandmother's Six Dresses, 2016, fabric. 75cm X 75cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Taqwa: Yes, but the Khorfakkan I grew up as a child is slowly changing. It makes me realize this place that I am living in now will change again. So I just want to preserve what is around us and show it to the people.

MEA: What was something that you saw here that inspired you to pursue further studies in the university in the arts?

Taqwa: My parents used to make us find a hobby and practice craft making that our grandparents did and this inspired me to further explore this. Right after that situation with my sister drawing my homework, I was interested in art. I wanted to explore the art field and find out how big it actually was. I had no idea that there were huge places where artists gathered and created art together. I just would practice and read about the basic movements I learned in school. I remember there was an Egyptian teacher in my grade school who would take all of the top artists to local competitions. She would take us out of the classes (which was always the best!) and she would take us to these competitions. I really enjoyed us drawing and making art together.

The artist. Image courtesy of the artist.

MEA: Was your transition to university difficult for you?

Taqwa: Yes, of course. When I went to university, everything was in English and it was difficult at first. I had no idea about these art historical movements towards our third year. And that’s when I realized I learned about these movements in Arabic when I was younger in secondary school. It must be the language barrier that caused me to forget about this.

MEA: When you were in secondary school, did you develop any early artist friendships that continued to university?

Taqwa: When I graduated, everyone shifted to another field. Most of my friends shifted from painting to comics like anime.

MEA: When did you learn about the history of the UAE art scene?’

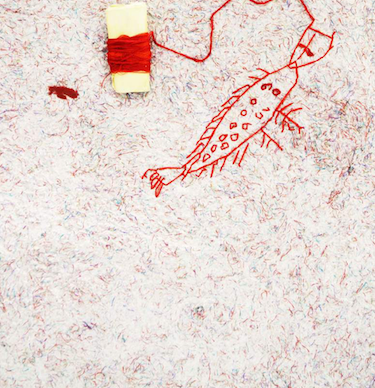

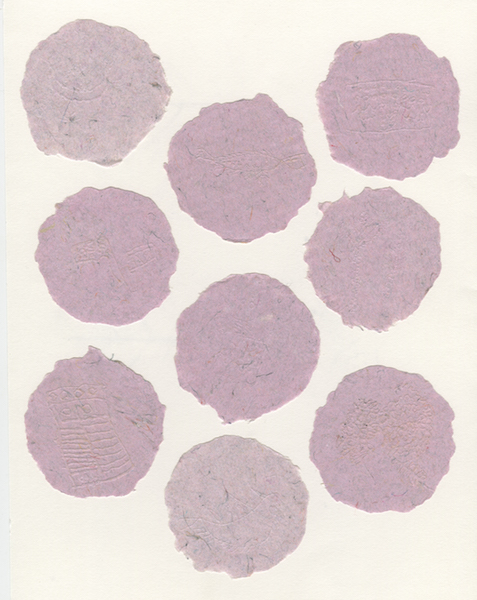

My grandmother's Six dresses, 2016, Talli thread, Glass jars, paper plup, various dimensions. Image courtesy of the artist.

Taqwa: I was in my third year and we had a course “Emirates PhD” which introduced us to this history of the art scene in the UAE. They took us to the Bastakiya area, Sharjah Art Museum, The Barjeel Art Foundation, Tashkeel, and the Sharjah Art Foundation. I remember we went to Alserkal one time and I met the artist Mohammed Kazem. I had no idea who he was except that he was an artist and had really cool work. Sheikha Mazrou was there and she was talking with him and I’m standing behind them thinking ‘why is everything so intense…everyone is stopping and talking to him. Who is he?’ When we finished the course I had to write a report. Unfortunately I didn’t write my report on Alserkal, but I wrote about the collections of Sheikh Sultan. My professor was Thaier Helal and they printed a lot of artworks of Emirati artists and they told me ‘see you’re from Khorfakkan’ and these others are from Dubai. You should be influenced by them!’ And that is when I started to be more interested in art from the Emirates.

MEA: How did you do it? Did you meet all of these artists, and go to their exhibitions?

Taqwa: Well the resources were so limited because the college didn’t have much written material on this. But it was through meeting these artists at art events that I got to know more. saw three books in the college library: one called Khamsah written by Hassan Sharif. It took me three months to read it. I googled Hassan and saw a video of him working on his art. He kept on repeating the same exact movements, stitching cloth together and piling it in a mound for about 10 minutes. At first I wasn’t interested but then while I began to advance in my education I realized that this man was a genius. I kept on searching about him. I saw these small videos and read back and front these books. They didn’t even have a title. Shaikha Mazrou and Their helped me a lot in terms of research. I learned more deeply about the history though after graduating and when I participated in my first exhibitions. I met all of these artists at this exhibitions. I attended all four of the "Is Old Gold" art talks with speakers like filmmaker and writer Nujoom Al Ghanem, artist Fatima Albudoor, Hind Mezaina, Mohammed Ibrahim and Alia Lootah. When Nujoom Al Ghanem was talking about Tashkeel magazine and the Flying House, it inspired me to learn more about these groups of artists. I talked more with the curators and saw how important this circle was. After speaking with these older artists I can’t help but to tell myself Taqwa, ‘you are doing is nothing! You have to work harder.’ The curators helped me a lot though, since they know I’m new to this field. On the exhibition openings I was surrounded by some of the first Emirati artists in the UAE and I couldn’t believe that I was talking to them in person. When I met Mohammed Ibrahim I didn’t think he would even remember me, but he did which meant a lot. I also found out my father knew about Mohammed Ibrahim. I took my father to Abu Dhabi Art last November and he met Mohammed Ibrahim and it was surreal to hear them speaking about knowing of each other. Khorfakkan is really so small. My father also knew artist Mohammed Astad from Khorfakkan, they were friends since very young.

MEA: What was your first series that you created in the university?

Taqwa: My first artwork was a bounded book. I learnt the process of bookbinding in university, and through this I not only wanted to present it as a book but also as an artwork. I wanted to highlight how it feels to live in Khorfakkan. At the same time I was learning about older artists like Abdullah Al Saadi and Mohammed Ibrahim who all live very closely to me and saw how our environment was affecting them. I was so interested in this and I then made a huge book with drawing and screen prints and I threw the book into the sea. The sea symbolizes Khorfakkan and so I threw it into the sea and came back after a couple of hours and found the book with ridged leather.

MEA: How did it feel to throw the book into the sea?

Taqwa: I felt something changed within me. At that point I really started to collect things and keep it with me. I wanted to save all of these elements, because it was really precious to me.

MEA: And this is where you began to explore my your roots?

Taqwa: Yes I tried to connect with my family, and to understand ‘where am I from, what is my past?’ I became closer to my parents and grandmother. I traveled with my parents to see my father’s first home he grew up as a child. I never have been to that neighborhood before. I started taking pictures, but I wanted something more physical than pictures or writing. I wanted something that I could see.

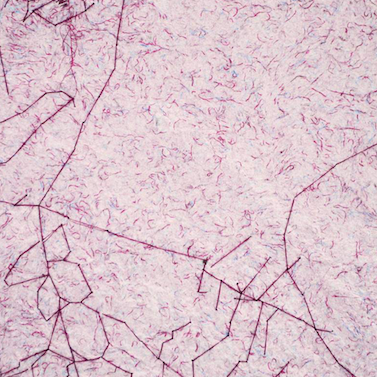

MEA: How did you think of this idea of going to your grandmother?

Taqwa: Before going to my grandmother I was writing a lot at the time. I was surrounded by my nieces and nephews and I would let them draw and I found their works to be so abstract and communicating a type of language. I realized what if I made my grandmother draw? What would the differences be between the children and an elder? Couple with this question I also went to her to lear more about my family’s history here. Since she doesn’t know how to write I told her she can draw whatever she wanted to tell me.

MEA: When you wanted to put your grandmother on the spotlight, was she hesitant or excited?

Taqwa: No, in the beginning she dealt with the telli, traditional Emirati handicraft. I would try so hard to show her I was a good granddaughter and learn how to make telli with her. I learned so fast, and by that time we really connected with each other. We really got close with each other, and from there I gave her these papers and I asked if she could do something for me. She was very open, and right when we started she was laughing. My grandmother started drawing and while doing this she told me about her past. She told me during the school her professors told her how quickly she could learn. When she would point to different parts of her drawings, she would tell me a story about that exact point. I was so overwhelmed, it felt like such a Picasso drawing.

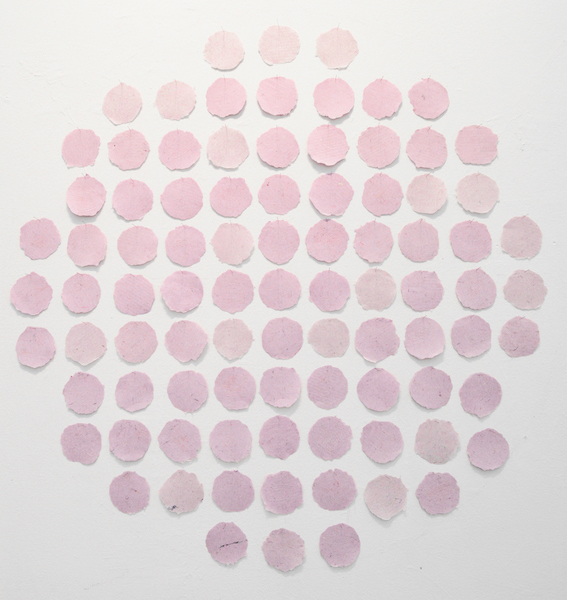

I continued these conversations and every time I would visit her I would choose different elements from her house. I then started to experiment with the paper materials. I used her dresses rather than the regular paper making process. I realized I was trying to make connections but in a different way. I then started to make connections with what surrounds me, like the local things. I realized that my works were a derivative of my culture. People would tell me this is such a classic way of recording your traditions, but I defended myself and knew this was so important. They would tell me stop recording things in such a straightforward way. Such as mokawer, which is a traditional cloth. I just want to say this cloth is an important part of my life and I don’t have to explain it to them in any other way than just showing it. At that point I was so frustrated because I had no idea how to present my work….

(pause) this feels so great because I never told this to anyone before!

MEA: I’m sure this intrigued your professors?

Taqwa: I showed my professors and they were so happy because they saw a culture and a history, but in a very conceptual way. They loved it and they pushed me to develop it more. They knew I needed to focus more on the practice of paper making. At that time no one else was doing paper making. I was really one of the first students that went into the paper making room, and I had to move and clean everything to use it.

MEA: Why do you think?

Taqwa. Courtesy of the artist.

Taqwa: Most want to do sculpture, painting or printmaking rather than the paper making. Some classmates thought paper making was just a technique that you needed to learn to put on your CV and after that, khalas you don’t need it anymore. But my professors pushed me farther with it, because the process was so intertwined in my work.

Sandstorm blows the door open…

MEA: What materials do you use when making paper?

Taqwa: My professor taught me through cotton and abaca sheets (banana sheets), blended and processed. But at the same time I also learned through YouTube about the Japanese paper through individual fibers. Then my professor taught me why I don’t use a material from my culture? He guided me to use my grandmother’s dresses, traditional Emirati cloth called Mkhawr. From that point I was confident that I could materialize any memory, any idea through these papers.

MEA: I wanted to mention there’s a famous Qatari artist, Yousef Ahmad who also practices the Japanese style of paper making too but by using compressed date tree wood.

Yes I know of him! Dr. Mohammed Yousif at my university told me about that artist. I hope I can meet him soon.

Taqwa: I think he would be very important for you to look at. He was living in Japan for a bit, and he knew right away that he didn’t want to use any foreign materials in his work and he decided to grind his pulp from the date trees.

My print making professor was working in the paper making room on a piece made out of ghaf which is considered national tree of the UAE. I was somehow surrounded by creative people that would inspire me. I really miss being around students in their studios and the repetive motions and processes of creating works. I miss learning with professors, especially those that are from the UAE and use their local materials. This has all taught me that I must care about making my art through repetitive processes and using my local environment.

At one point during college I realized I didn’t want people to see my work as a traditional Emirati. I wanted to say, as Mohammed Ibrahim said before - ‘You are an artist from the Emirates, but it’s not “Emirati art.”

MEA: Yes and I think you can just look at your work material-wise and see the physical experimentation you did on it. It doesn’t have to be this cultural signifier, or this Emirati heritage heirloom. Like Hassan Sharif and all of these artists were influenced by other non-Emirati artists like Marcel Duchamp.

Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim. Courtesy of Suzy Sikorski.

MEA: Did you feel some of your friends were going through the same thing during university?

Taqwa: Yes of course. It gets very confusing when you think you need to do something that’s part of your culture—should it be straightforward? Mention small clues to show you’re Emirati, but it really confused me.

MEA: What prompted you to meet Khalil Abdul Wahid when I met you at Abu Dhabi Art in November 2016?

Taqwa: During my last year of college we visited the Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation’s ‘Portrait of a Nation’ exhibition in Emirates Palace in Abu Dhabi that same year. I saw Azza Al Qubaisi’s work, which was a video that shows her talking about her artmaking. I really enjoyed the precision of her jewelry making process. At that time I got more in touch with ADMAF, and I even became the first runner up for the Gulf Capital-Abu Dhabi Festival Visual Arts Awards in 2016.

I really wanted to meet Azza from this and I knew I needed the confidence to just step up and introduce myself. ADMAF sent me an invitation if I wanted to do a portfolio review with these artists such as Khalil and Azza. When I did some research for Khalil, I realized he was one of Hassan Sharif’s students and from then on I knew I needed to speak with him.

MEA: Khalil definitely has a knowledge of the older and younger artists. It was so inspiring to witness two local artists finding that common bond and part of a network of artists that know about this UAE art history.

Taqwa: I find every artist has their different personality too. They all have their different resources and I realize I need to listen and respect everything that they say because they know more than me.

MEA: You just graduated and you are used to being in a classroom, and I think it was great to meet you speaking with Khalil because you’re expanding your horizons.

How were you able to publish this book on your final project?

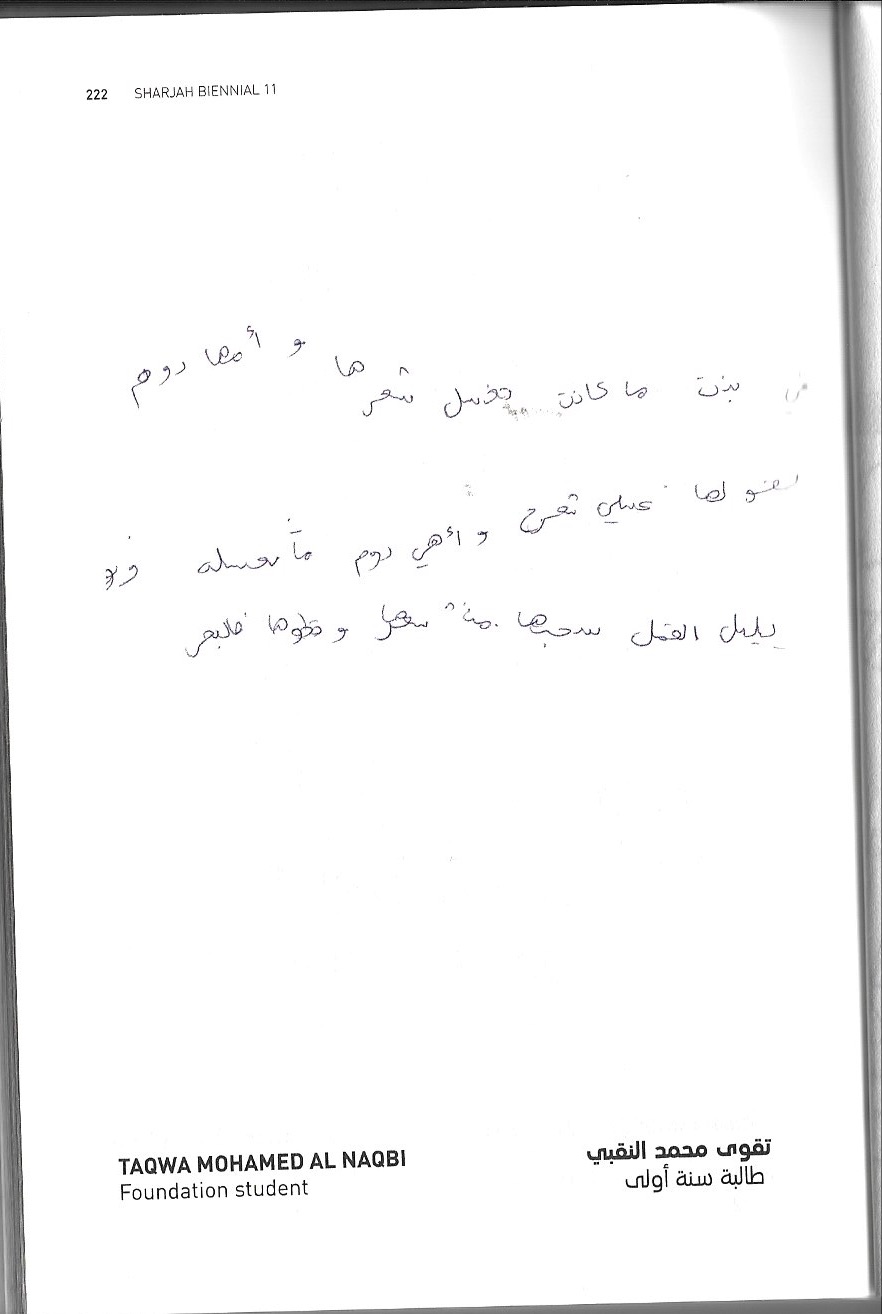

Taqwa: It was two years after finishing “My Mother Can Draw” before I published my book with Sharjah Art Foundation. I’m really thankful for their support with this. I wanted to show people these drawings but they were too close to me to just scatter throughout the UAE. One of my professors told me to see if I can get these works published into one small book. When I was looking at the catalogues I saw Nasir Nasrallah’s book that he put all the drawings he did for the Sharjah Biennale 13, the Story Converter.

**Note aside: Nasir Nasrallah created The Story Converter for the Sharjah Biennial 11. The audiences were invited to write something personal on a card hidden inside a custom-made black box without seeing what they were writing. Nasir used these written texts to create a new doodle drawing, combing this donated material with his own visual experience and thoughts. The resulting drawings were displayed besides these anonymous writings, the input and output of the black box, a virtual machine. In exchange for their participation, the audience received a handmade notebook created from recycled paper. Text taken from Nasir's website.

Nasir Nasrallah, The Story Converter, Sharjah Biennial 13. 2017.

Nasir Nasrallah, The Story Converter, Sharjah Biennial 13. 2017.

Taqwa: My story in Nasir’s work was about a story my grandmother used to tell us when we were young. It is about a girl who doesn’t wash her hair and one night lice in her hair dragged her out to the sea.

I visited Bait Al Shamsi with visiting students from Eastern Carolina University. It was my first time I met Nasir Nasrallah and he showed the book with all the drawings in his catalogue. While looking at his drawings I realized that he showcased one of my written stories! It was really special to see it.

MEA: When you want to discuss about your artwork where do you go?

Taqwa: First my professors, but recently I haven’t gone that a lot because I’m trying to find a job. I don’t have a lot of connections with artists, but I would love to. Thankfully I can speak with Abdullah Al Saadi, Mohammed Ibrahim, Khalil Abdul Wahid and Shaikha Al Mazrou. Shaikha was actually one of my professors. Now that I can to these Emirati artists though I go straight to them which is really amazing.

MEA: Now I think it will make your perspective so much wider, and not only in terms of speaking with these artists, but it’s innate in you because you’re touching the heart of your history and your family. I guess I only opened some door that you didn’t know was there. For me, I’m not an artist, but this concept of looking back into history has become so important to me. It’s about speaking of history through objects and material, for me through writing and photographing but your work shows me there is many more ways in doing that.