This article was originally printed in Canvas magazine.

Senses of identity and belonging, of heritage and inheritance, loom large under conditions of constant transformation. In a place that is as young as the UAE, artists find themselves grappling with the recent past as they look towards the future. This is a personal story of how some of the leading Emirati artists have worked to fashion a path through an often fast-moving and potentially bewildering landscape of change.

Words by Suzy Sikorski

A collection of miniature objects, a treasure trove of uprooted tree trunks, an eclectic menagerie of rocks, old tattered catalogues, dusty exhibition awards and rusty metal wires. These are the ephemera and elements of material culture that I’ve found during my UAE studio visits over the past couple of years. Emirati artists, whether their medium is oil paint or found objects, house their memories within studio spaces that are, for the most part, their artistic haven amidst a rapidly changing environment beyond their doors.

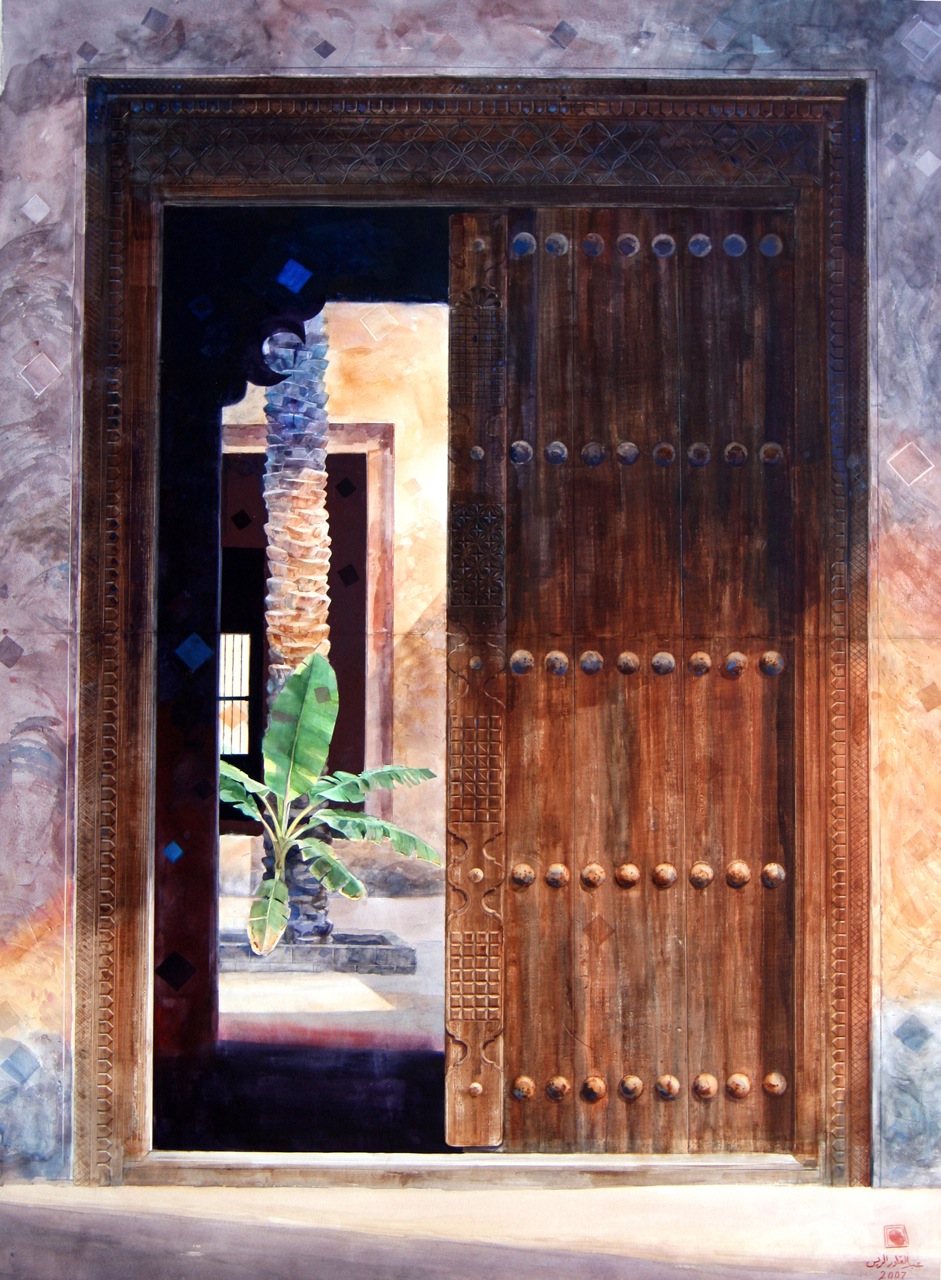

Abdul Qader Al Rais. From the Yesteryear series. 2007. Watercolour on paper. 157 x 207 cm. Image courtesy of the artist

To remember the encounters that I’ve had with a particular generation of Emirati artists, one that came of age between the late 1970s and 80s, is to invoke the inviting scents heavy in the Khorfakkan and Madha air, groves of lemon and date trees, the buzzing of old air conditioners in a quaint Sharjah villa and the persistent traces of turpentine and thick oil paint inside cloistered workshops. In much the same way that Proust found memory in sights, smells and sounds in his iconic novelÀ La Recherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time), these artists’ works and ateliers function as sites of excavation, alluding to motifs of remembrance and place. I have been charting the course of three decades of UAE art history (1970s-90s) withinthe con nes of these studio spaces – initially for my Master’s thesis and then in lm documentation. Mostly drawn to an older

group of local artists who worked with installation, land art, painting and sculpture, I found that their pioneering practices, which were of a physical nature, resonated the most with the multilayered realities of living in the UAE.

Against the backdrop of a modernising landscape that has undergone a dramatic transformation since the 1980s, locally based UAE artists have been confronted with relentless change both externally and internally. Their familiar ‘spaces’ were in constantux, at times because of physical relocation across the UAE, andother times as their practice and focus shifted, transitioning over time within their studios, some of which were annexed to their homes while others were abandoned and repurposed rooms that became places of experimentation.

Mohamed Yousif. Camel Movement. 2009. Wood and leaves. 116 cm x 150 cm x 30 cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

In a way, one can view an artist’s studio as a living archive or repository for objects and tools that serve as a means of documenting man’s presence within the shifting environment, anda place in which to collect ndings in nature. Many of the artists’gardens seemed an extension of their artwork, while their interiors mapped their daily lives through the arrangement of objects, the smells of raw wood and ocean decay. As Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim states, “Nature is everywhere, even inside your house, butit just depends on how you can feel your way through and nd it.You don’t have to spend the time in the mountains, desert or sea.”

Sharjah-born Mohamed Yousif, one of the founders of the Emirates Fine Art Society, only works outdoors. He gathers his subject material in the garden he cultivates adjacent to his studio space and produces works that are inextricable from their source in nature. “All of my works derive from nature,” he explains. “When I collect different elements from a tree, whether wood or leaves, I am attuned to the age differences between the various trees. Just as humans exist in generations, so too do plants, and my work attests to this synergy in life cycles. For this reason, I want the weather to interact with my artwork. I prefer for them to be seen in nature, rather than imprisoned in galleries.” Yousif incorporates the roots of trees in his practice and many of his whimsically crafted wood sculptures comprise palm tree fronds that are symbolic of movement in the world and in the environment.

Abdullah Al Saadi. Alphabets. 2018. Image courtesy of the artist and Abu Dhabi Art.

Artists originally from Khorfakkan, such as Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim and Abdullah Al Saadi, found a degree of transience in their art-making practice, as they constantly moved between the city of Sharjah while also tucking themselves away in the mountains. Al Saadi for example, moved from the side room of a mosque in Khorfakkan to the Folk Arts Association and then to the public library (with Ibrahim and the poet Ahmed Rashid Thani), later turning to Sharjah’s Emirates Fine Art Society house for his practice. Al Saadi has built his current studio himself,next to his family home. Eccentrically lled with framed deadinsects and stones meticulously arranged in order of height,it also contains a private library lled with old catalogues andEnglish literature, revealing his love for language. His poignant work My Mother’s Letters (1998-2013) features a documentation by his illiterate mother, who would leave objects in his studio as a way of letting the artist know she was there. It is a language expressed through symbols, carefully selected by his mother to confirm her existence by using her own alphabet. Such are the relics of an abandoned culture.

Abdullah Al Saadi. My Mother’s Letters. 2018. Image courtesy of the artist and Abu Dhabi Art

For Ibrahim, who wraps rocks in wires, scatters his land art installations in the ocean and cakes plastic containers with stoneand clay, straw and papier-mâché gures, his works embodyorganic primordial shapes and symbols. Composed out of natural materials, he often returns them to their original environments.

Finding solace within a certain degree of isolation in their natural environment, both Ibrahim and Al Saadi create their own artistic language, finding a mode of expression in fabricated symbols (in the case of Ibrahim) or diary-like writings and invented alphabets (with Al Saadi). Both artists produce work that is rooted in their ability to contemplate and embody their surroundings in their practices.

Abdul Qader Al Rais, one of the oldest and most celebrated artists from Dubai, has been producing a body of work from painting en plein air, finding beauty in the landscapes throughout the Emirates and piecing together on the canvas his memories of growing up both in Dubai and Kuwait.

Depicting historic buildings before they were destroyed by modern development, his work can be seen through the lens of ‘romantic realism’. Meticulous renditions of the coastline are intertwined with representations of local architecture almost with a sense of urgency as Al Rais witnessed the landscape evolving at an exponential pace. He began his artistic practice in Kuwait’s Marsam Al Hurr studio (the Free Atelier, which a lot of modernists in the region frequented) in the 1960s at a time when artists there were very advanced in their training, then returned home to paint in the Bastakiya alleyways. Widely recognised for his elaborate depictions of old wooden doors and watercolours, Al Rais captures inviting scenes of traditional architecture in renderings of soft light and ochre tones.

Whether located on the coast or inland, these separate and often private artist spaces continue to drive the region’s creative pulse. Each tells of an individual’s unique relationship with the land, its culture and history. Finding a sense of belonging through an environment that keeps shifting, these artists did not lose their bearings as they navigated their art practices and developed a shared sense of stability and ofpermanence – of rootedness to the place in which they createand produce. It is a place that is both inside and without. “I like to keep my studio door open, even in the summertime,” says Ibrahim. “I need to feel some contact with the outside, because it feels like I’m living in a closed box in here...” Almost lyrical, their collective approach is indicative of a cultural topography and an endless pursuit of the natural elements, materials and vernacular that make up the sense of home.