Kuwaiti/Ukrainian artist Amani discusses the evolution of the dowry and its deeper cultural meanings in her work "Codes of Conduct".

Currently finishing her MFA at Goldsmiths, University of London, I had the chance to Skype with Amani while she was installing her degree show opening this week!

Amani AlThuwaini.

Artwork of the Week: "Codes of Conduct"

1. What early childhood memories do you have of Ukraine?

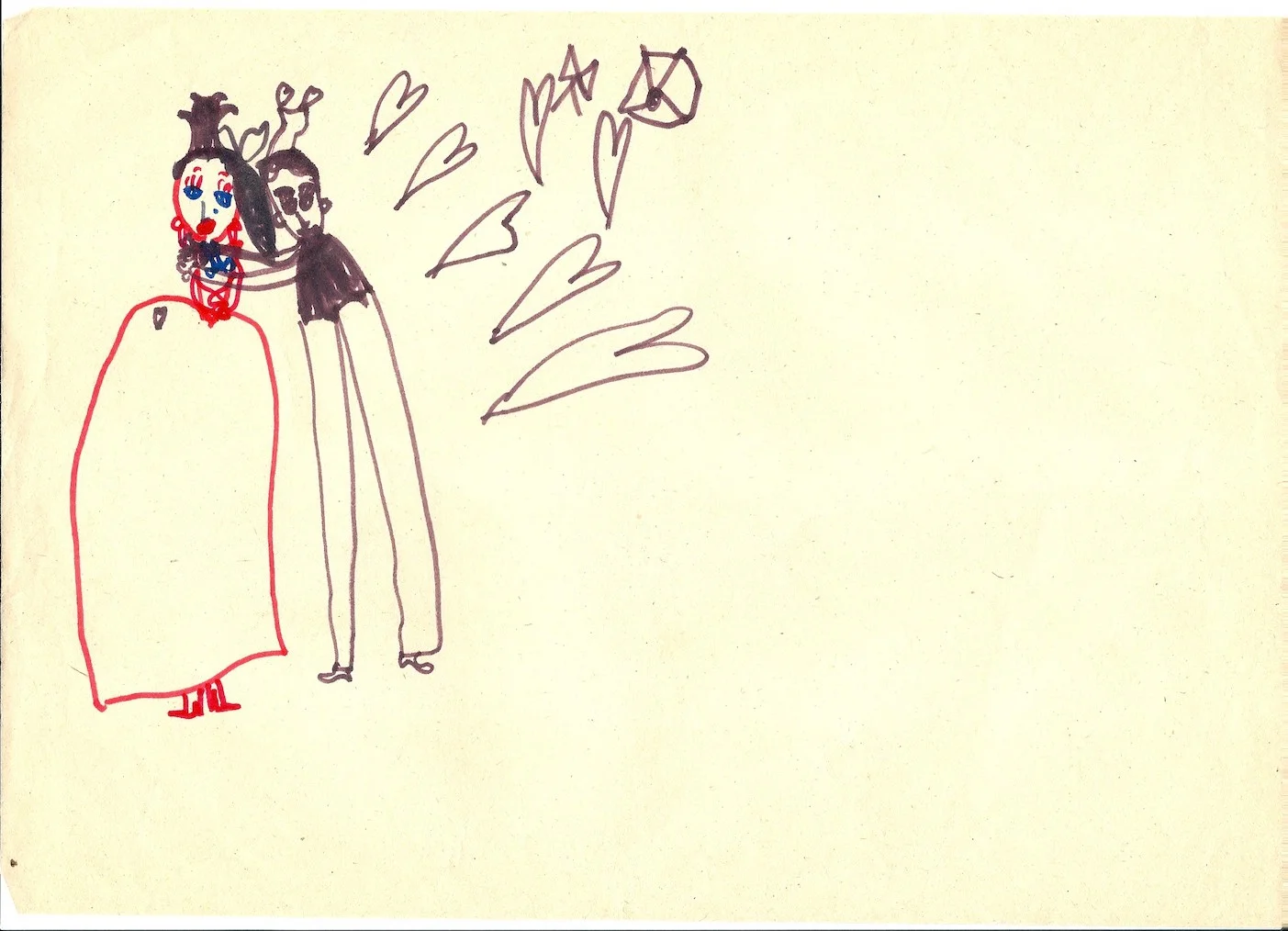

The most vivid memories of my childhood in Ukraine is constantly watching fairytales ("skazki" in Russian) such as The Nut Cracker (see below). It still makes me emotional every time I watch it until these days. Watching Russian 'skazki' influenced my childhood drawings which were mostly drawings of love and weddings including brides with long braids, folk headpieces and big dresses. I remember waking up an hour earlier every morning before my siblings woke up just to be alone and draw. This was important to me.

Film still from "The Nutcracker" (Shelkunchik)

Amani's early childhood drawings.

2. How did you choose to work around the traditions of Kuwaiti weddings?

Growing up between love fairytales in Ukraine and marriage traditions and rituals of Kuwait is like bringing the heart and the mind together in one entity. Marriage is usually more intuitive in Ukraine while in Kuwait it is structured, taking certain steps with certain logic. When I got married 3 years ago, it felt like bringing a fairytale and reality together and in my head it was the one place my two backgrounds came together. Those steps leading to the wedding were very new and overwhelming for me; 'khitba' for women (women's proposal), 'khitba' for men (men's proposal where 'dazza' (dowry) planning takes part), dazza, 'milcha' (signing the contract), 'milcha' celebration then wedding. Criticism from older people was inevitable. For example, I was criticized for wearing a black dress on the day of receiving the dowry. I was also criticized for not having ''enough'' flowers in my wedding. I came to realize the normality of these things and started paying attention to my friend's and cousin's stories and collecting them and this was the beginning of the series of works. The first piece I made was Dazza which is an observation on the transformation of marriage traditions and the importance of ''display'' and image in the content of the dowry/dazza gift. (See image)

Dazza (The Dowry) 2016 Installation; woven fabrics, cowhide leather and plexi glass; 240 x 90 cm

3. What are you trying to tell people about the dowry process in “Codes of Conduct”

With the piece Codes of Conduct, I want to convey how each time has it's own set of norms or codes when it comes to dowries. However at the same time, these different histories merge and come together. This is why dowries are an important physical form of identity. I am specifically tackling pre-marriage gifting; it is not just a form of exchange but also the beginning of a relationship between two families and this is done through forms of hospitality and giving. The piece resembles two different traditions of making--one is textiles which resembles the 'buqsha,' bundle of fabrics which was one of the early forms of dowry in the Middle East. The second tradition of making is gifting on trays and the use of laser cutting and contemporary technologies in the marriage gifting context. The 4 kufic texts on the tray resemble pre-wedding traditions: Yalwah, jhaz, buqsha, dazza.

4. How did you research about this?

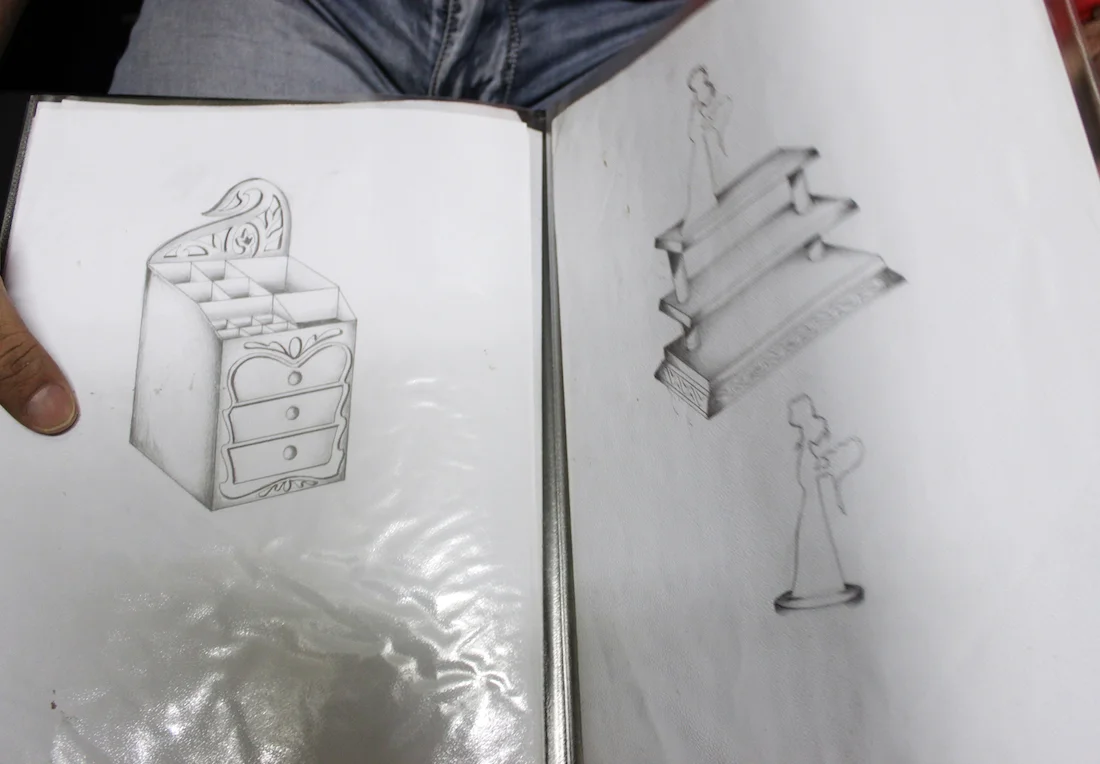

Designs from a Dazza making shop in Kuwait

The research was done through interviews with women from different generations and collecting stories on dowries of each time. It is interesting how humans bond with objects and convey the meanings they signify in every story. The works become another form of archiving these histories which are under documented. Another research method I used was looking into different Islamic traditions and mapping the trade and travel of goods and how they affected the content of mahar and dazza gifts. It is highly linked to crafts such as kilims and sadu weavings, as well as wood carving and box making. A helpful tool for research as well is looking at the industry of dazza gifts as a whole in Kuwait. Sometimes they're flower shops who custom make dazza's and sometimes they're shops specialized in the making of dazza gifts (image 5.) I stay in touch with them and observe their Instagram accounts very closely as well as how it's linked to consumer behavior.

5. Can you explain how the technical process of “Codes of Conduct”

Codes of Conduct was made in two parts, one is the 'buqsha' bundle and one is the wooden tray. The textile piece in the centre was made by sewing different Indian fabric strips together in the shape of a bundle. While the tray was made in three steps, the first was designing the Square Kufic text in the background using Computer Aided Design (CAD), then laser engraving this design on the piece of wood, and finally attaching the tray handles on the sides.

6. You had some interesting jobs in the past, can you name a few of them?

My first job was when I was 18 and I worked in Sultan Centre Bakery in Kuwait. Then I had a few amazing experiences such as visual merchandising in Nike Kuwait, sales and interior design in IKEA Kuwait, and graphic design for retail. I also worked as an architect in a few firms in Kuwait and taught kids arts and crafts. One of the latest experiences was working as a teacher assistant in Kuwait University in drawing and interior design classes. It's interesting how all these experiences come together in the end as I deal with consumer culture and the domestic environment in my work.

7. What’s next for you after graduation from Goldsmiths, University of London?

After graduation I want to do a solo show on the works I made during my two years in London in the same research topic I talked about earlier. I'd love to also work on a few collaborations in mind with other amazing artists who are in Kuwait right now. Another thing I'd like to do is bring people I've met in London together in a show, my Goldsmiths colleagues and artists from the Gulf. I'm very excited but also anxious about what's yet to come!

Amani's Degree Show is from 13 - 17 July at Laurie Grove Baths Building at Goldsmiths, University of London.