“Children jump while playing…men jump from parachutes and people jump at the beach. (…) In this performance, I jump in Hatta desert. Many people jump in different ways. So why shouldn’t I jump in a desert?”

Hassan Sharif in his studio. Image courtesy of Maaziar Sadr.

Note to reader: this blog post was originally written just before Dubai lessened its 24 hour quarantine. My quarantined hallucinations have diminished with the occasional walks outside but are very much still part of my reality!

My hallucinogenic visions brought on by week 7 of quarantine life have now been reduced to an assortment of mundane activities and exercises. The daily visuals have been orchestrated by the repetitive shapes and lines found in my domestic landscape, at all angles and at anytime of the day. I’ve become a performer (at times parallel to Marina Abramovic), however with my own no-show rehearsal save for a few childhood stuffed animals and a handful of lucky neighbors who can probably see me shuffling away during my cleaning sprees. Channeling my inner Charlie Chaplin, I occasionally break out in dance with my vacuum cleaner and take out my rusted Gemeinhardt flute to warm up with a few scales.

Marina Abramovic, ‘Confession’ (2010). Image still from 60 minute video.

While my poor attempts self-auditoning as the next singer, dancer and flautist are all colliding into the same room (with no call-backs yet), my overall sense of real time and measurements, in actuality within a very timeless-ness void of over a month, have been adhered to so systematically. My internal clock is now accustomed to 6:30am wakeup calls that I no longer need an alarm; just as easily I wake up, I can also fall asleep in the evenings at the drop of a hat - counting the self-isolating sheep prancing into Narnia as I walk into my vividly illustrated dreams throughout the night. During my days, I tap away on my apartment tile floors pacing my moments through these repetitions, trying hard to not step on the ‘in-between’ cracks like I had done as a little girl. I carefully measure one spoonful of Turkish coffee mix to jumpstart my mornings, sipping my piping cup while I record my thoughts and daily rituals ever so carefully between the lines of my journal.

My sight into other spaces and places both physically and digitally presents itself within a menagerie of geometric shapes - I catch the sunset through my floor-to-ceiling square windows and speak with colleagues and friends through a rectangular panel of a device. In my downtime, I step outside onto my small balcony, and sit and peer through the metal bars into the private spaces of other quarantine-ers in their sky-rise cubicles. I am always paying careful attention to those catching a few moments outside just like me too, in case they are asking for an encore for another performance of mine ..

Detail of Hassan Sharif’s ‘Body and Squares,’ (1983). Photographs mounted on cardboard, 84 x 59.5 cm. Guggenheim, Abu Dhabi

This Marie-Kondo lifestyle of systemic organization has probably existed even before the quarantine, but has exponentially heightened during this time in isolation. My awareness and attention to everything around me has grown. The churning of the refrigerator (its signal that I need to do some online grocery shopping, just as a stomach growls for food). The rattling of the ongoing AC, the occasional water taps from the kitchen sink, and the ‘coo-ing’ coming from a dove’s nest above my apartment filled with a family of birds that begin their singing performance after 6am. These very close four walls have forced me to have an insanely acute awareness of my environment as I now embrace all of it within its Feng-shui. I absorb the sounds, smells and energies that ricochet in such a tight space as I experience them simultaneously complement each other at full force.

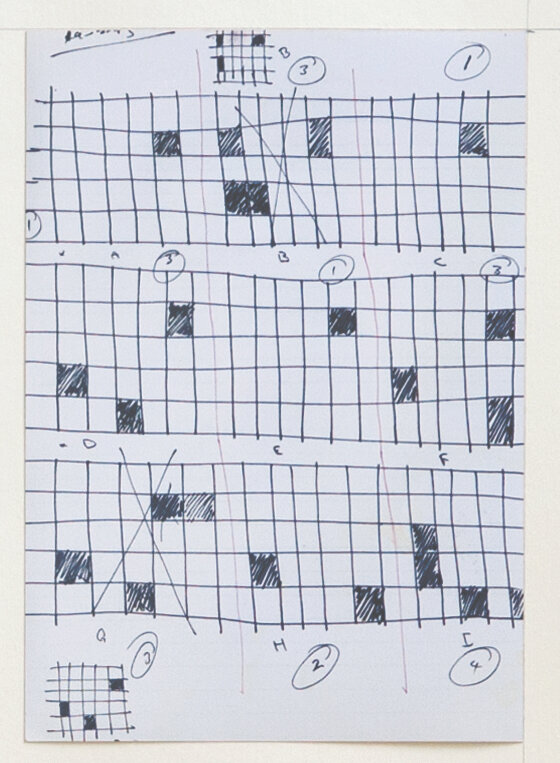

Staring down at my cubist tiled landscape below has reminded me of someone who had experimented a lot with the mundane in the private and public realm— that of Hassan Sharif (1951-2016). These beige tile floors are the catalyst to this blog post, and I really can’t help but to think of Hassan’s performances with little to no audience in the early 1980s in Dubai; these performance acts are credited as one of the first in the entire Gulf region. In one work he lies on the floor in a man-made grid measuring as ‘long’ as himself (25 squares measuring total 165 x 165cm), moving around as if he’s on a solo ’Twister’ game challenge, maneuvering himself in to find the maximum numbers of squares he can touch with the most combinations. I haven’t tried this one yet but can use some spice to my daily activities and decor rearrangements.

Hassan measured and documented himself jumping, digging, walking, swinging and throwing stones - one could’ve thought he was training for the high-jump in track and field or the next triathlon. He eventually displayed these works with a sketch and writing on the general plan of the activity that correspond to the displayed photograph of himself doing the activity and the eventual outcome on a grid. He occasionally would also complement these performances with voice recordings, such as speaking on a swing set.

Hassan Sharif in 1976. Image courtesy of the Artist Estate.

Keeping this in mind, a whole range of ‘do-it-yourself’ projects rooted in mathematical and geometric systems suddenly presented themselves to me in my domestic landscape of kitchen utensils, excessive amounts of books and tiles that are expansive enough for me to sprawl out like a cat on the floor. I’ve measured myself on the scale and with meter stick, but it seems right to know how many tiles my body can occupy in contorted twists. Luckily no conversations in a toilet yet! (In 1983 Hassan visually documented a meeting with his English language tutor next to a toilet at Byam Shaw School of Art)

Noted as one of the first conceptual artists from the UAE and greater Gulf region, Hassan sought to dismantle the notion of the ‘high class’ definition of art and explored this through his performances, objects, 'semi-systems' and experiments that made up his practice. Hassan is a pioneer for his roles as artist, educator, critic and writer and his exploration into the conceptual art movements with a life that traversed between the UK, UAE and all that lies in-between. Exploring elements of repetition, landscape and the body, his work tackled underlying notions of the political, along with the effects of modernization, exponentially felt in the UAE just within the last 30 years and the ensuing consumerism, manufacturing and commercialization that society faced. Continuously experimenting and revolutionizing his art practice, he simultaneously educated the art scene, while his works never ceased to embody all walks of life. Constructing works out of rope, rocks, cardboard, thread, needles, shoes, and backpacks, he handpicked this precious cargo from garbage dumps and throughout the buzzing markets of Satwa, Deira and Bur Dubai. Only then to return to his intimate studio space, working at them endlessly, carving his works into monumental or miniature beings. As an educator, he translated art historical books into Arabic for the local arts community and helped in the establishment of the Emirates Fine Art Society in 1981; he had a weekly column in a magazine, and was responsible for the art historical content in the Art Society’s magazine ‘Tashkeel.'

Hassan Sharif, ‘Black and White,’ (1985) oil on canvas, 90x90 cm. Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.

On an art historical level, his formal ideas were rooted in avant-garde modern movements of those such as Marcel Duchamp, and others within the Dada and Surrealist art groups. In line with my blog post today, particularly his performances and systemic drawings were rooted in British Constructivism and Fluxus movements that were roaming wild when he studied in the UK in the early 1980s. British Constructivist theory sits along a continuum of reconstruction attempts in art architecture, and design since the 1930s as creatives sought to transform aesthetics following WWII. The movement was noted for embracing the environmental impact and architectural implications in artwork (to see Ben Nicholson, Naum Gabo and architect Lesly Martin). In the 1950s, artists like Victor Pasmore, Kenneth Martin and Adrian Heath carried on the additional phases of Constructivist thought, seeking to redefine artistic theory and aesthetic potential of geometrical systems. These artists articulated art making through a scientific and mathematical sense according to objective principles and incorporated a participatory engagement with the viewer. Works were not just to be appreciated as ‘beautiful object's.’ Noted in both US and UK art circles by some as ‘the least fashionable kind of modern art’, Constructivists looked at these works in both an intimate and human scale (quoted from British art historian Alan Bowness in 1963).

Simultaneously complementing this group was a larger movement of the Fluxus school that prioritized intermedia experimentation, that originally started in New York in the 1960s, and then moved to Europe and Japan. Avant-garde artists included those such as Joseph Beuys, Nam June Paik and Yoko Ono. These artists built on Dada, Bauhaus and Zen principles, their works orchestrated by minimalist concepts and expansive gestures, connecting everyday objects based on the scientific, philosophical and sociological studies. With a sprinkle of humor it attempted to, as founder George Maciunas stated in its 1962 Fluxus Manifesto, ‘purge the world of this bourgeoise sickness..purge the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art’ and give greater importance to the process of producing than the finished product. The movement picked up in the UK in the 1970s and 80s at the time Hassan was there.

George Maciunas, ‘Solo for Lips and Tongue’ (1962) performance.

In 1974, Joseph Beuys spent three days in a room with a wild coyote for his performance, I Like America and America Likes Me.

Studying at the Byam Shaw School of Art in 1981 (the school later to be absorbed in 2003 by the prestigious Central Saint Martins), Hassan was introduced to a country deep into British Constructivist time. Studying under his professor Tam Giles, head of the Abstract and Experimental Department he was exposed to a highly educated art community that would become one of the greatest turning points in his artistic formation. Continuing to return to the UAE during the summers, Hassan carved out his experimental practice in performances beginning in 1982 that were categorized as the following by Polish art historian Paulina Kolczynska:

Minimalist actions performed in a desert

Performance linked to Sharif’s own mathematical drawings through Constructionist framework

Deconstructed familiar meanings through actions

While his systems incorporated the British Constructionist framework as he developed his work in drawings and performances, his performances were very much Fluxus inspired, greatly influenced by Kenneth Martin’s' ‘Chance and Order’ series, where the artist produced works ‘independent of his personality’ and instead let the matrices and rules provided ‘produce’ the work. His actions bordered on the simplicity, using the body as an artistic medium.

As opposed to Hassan’s London performances that were done in public with his other classmates and friends, those that were performed in Dubai were very private moments for the artists, done either at home in his house or garden, or in the Hatta desert with just a few friends and assistants who helped document the performance for him. In what seems like improvisation, his works embodied a poeticism that was carefully orchestrated denoted by a particularly calculated order and plan. Performances during this time include ‘Recording Stones’ (1983), ‘Swing’ (1983) and ‘Body and Square’ (1983).

Yet despite the fact that these performances were done with relatively few people, they still at its crux were meant to be disseminated to the public as a way of educating and cultivating a like-minded community. Which is something not far too different than many creatives in quarantine today sharing who are sharing their thoughts and ideas via social media. “From the very start, he realized that he could not simply work on art in isolation; the circumstances demanded that he should cultivate an audience, make friends, and new intellectual connections, and create a platform for creation, discussion and teaching of art.” (Hassan Sharif, Hassan Sharif: Works 1973-2011, Ostfildern 2011, p. 48).

Detail of Hassan Sharifs’ ‘Body and Squares,’ 1983 84 x 59.5 cm Photographs mounted on cardboard Guggenheim, Abu Dhabi.

In ‘Body and Square’ attempts to calculate the multiple combinations on how many squares the artist could cover in his physical positions; it includes a general sketch of the performance indicating exactly how it was documented. The grid with filled-in squares denotes the outcome of the calculations from the chance and order theory. These results denoted the particular squares that the artist’s body would be touching on the grid during the performance, each of the total 25 squares measured 165x165 cm, the artist’s height. In ‘Swing’ the artist chants performing a very basic activity - swinging, however here a stationary recorder captures the artist’s voice at high and low frequencies as swings. In ‘Recording Stones’ the artist documents all of the stones he collects and places them in an arranged order, leaving an open-ended question as to the particular meaning for the viewer.

“For instance, I speak while my mouth is full of bread. I take a sip of water. I eat more bread, speak, drink some more water, and so on, recording all the sounds. All the while I’m talking about serious things like politics and art, but it’s an ironic delivery, imitating politicians and lecturers”

Detail of Hassan Sharif, ‘Jumping No. 1,’ 1983 98 x 73.2 cm Photographs mounted on cardboard Guggenheim, Abu Dhabi.

With the passing of Hassan Sharif in 2016, his legacy continues to live on through the dedicated and tremendous efforts of the artist’s Estate, run by Hassan’s brother Abdul Rahim and Abdul Rahim’s son, Mohammed. Today the Estate works with three galleries around the world, continuing to archive and document Hassan’s work that has been seen in the monumental retrospective exhibitions and gallery shows.

Mid East Art had a chance to speak with Mohamed Sharif on his incredible work at the Estate, as he sheds a light on Hassan’s formative years in London and performances in the UAE and UK.

Sharjah Art Foundation's major retrospective on Hassan Sharif titled ‘I Am the Single Work Artist’ in 2017-2018. Image courtesy Sharjah Art Foundation

MEA: How have you been holding up in the quarantine? How have you been keeping creative and inspired these days?

Mohamed: I’m quite lucky with the kind of work that we do because I can definitely manage it online and I don’t need to physically go anywhere to get the job done. As for my inspiration, it has always been reading, whether in shorter essays, and novels in non-fiction or fiction.

MEA: How has work at the Estate been for you? What are some current projects you would like to share? How was the most recent Berlin retrospective received at the KW Institute?

Mohamed: The dynamics of my work has changed since Hassan passed away. There is always something to do, though. I am working with the 3 galleries, streamlining the archive material and maintaining the preservation of the artworks. This involves continuous checks to make sure the artworks are in proper condition. Obviously with the quarantine we can’t do this physically, but we are working on what we have right now in the storage areas.

The archiving actually began by my father in the early 1990s, without him really knowing it would result in an ‘Archive.’ He created an extensive and comprehensive list of every single work, including title, year, material used, the dimensions, with proper photographs. I later joined in 2009 and I had an intensive crash course in the history of art by Hassan. My entire understanding of art came through my uncle.

The most recent retrospective in Berlin was really a beautiful show. I am very pleased and I think Hassan would’ve loved it, especially to have displayed his work in this context and space.

MEA: Wow to receive a crash course in 2009 by Hassan, all during the same time the Dubai art scene was growing with fairs and the auctions. It must’ve been an interesting time for you. I didn’t arrive to the scene until 2015, and to this day I wish I could just be a fly on the wall during these key earlier years that shaped the country’s art history and to see how much the scene had grown.

Mohamed: Yes. I joined during the final years of the Flying House. The objective of the house was to give the local artists a platform and it did its job at the time. Hassan and my father, along with the other artists, established the house. My father turned our house in Al Qouz to showcase and preserve some local artists’ works. I met other artists like Mohammed Kazem and Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim, and I learned a great deal of things from them. I’ve been quite lucky.

MEA: Did Hassan have an alternative career in mind ever after returning to the UAE in the early 1980s? Do you consider his entire life was linked to his work as an 'artist' ?

Mohamed: Hassan wanted to be an artist very early on from the beginning. He knew the consequences and knew what that entailed, from how an artist lives and how they are perceived in society. He knew how tough it can be to be an artist, especially in our region. He was very well aware and he told us that this is the kind of life that he wanted for himself to be an artist. He didn’t see anything else but that. Art was his hobby, sport, spouse, children, oxygen… the whole thing.

MEA: What about these other jobs he had at ‘Al Akhbar’ magazine in Dubai producing caricatures, or at the Ministry of Youth?

Mohamed: Yes, he did do that in the 1970s. At the time he used that as a platform to exercise and explore what he wanted to do with the arts. This all happened before he went to London. After his first year in London, he realized doing caricatures is not what he wanted to do anymore.

MEA: Yes I see, I was reading an earlier interview with him and he had mentioned these earlier jobs served it’s purpose, but it was more of a temporary point and he knew when it was done.

Mohamed: Before even going to London he was buying art magazines in English from the local bookstore and he would be translating them into English. He had a very small idea of what art was outside the region, but when he went to London in the 1980s, and reading about artists like Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Beuys all while surrounded by a group of art students, he knew that was the calling, that this is what he wanted to do and this is the kind of work he wanted to understand. From that moment and early on his artistic career, he always knew he wanted to find his own voice.

MEA: I was just recently reading another interview with Hassan on how he loved seeing viewers interacting with his works, whether they were books or boxes- he enjoyed seeing them curiously opening the books.

Mohamed: Yes! He loved interacting with the works, many of his pieces make sound when you shake them and he wanted people to experience that. He enjoyed it because he thought that when you go to a museum, they don’t allow you to do that. They make the work like it’s holy. They put it on a pedestal, with a spotlight, and you treat it as if it’s a relic. Hassan didn’t like that and that’s why he said most of his work should be exhibited on the floor directly, especially the earlier ones. However it gets a bit tricky when transferring this to museums; in some museums you actually can’t because of preservation and other practical issues. Hassan came to terms with that at a later stage.

MEA: How were these performances received in society both locally and in the UK? Did he display or exhibit these works locally in the early 1980s? Did he exhibit them in London in Byam Shaw? If so, how were they received there?

Mohamed: Most of his performances that he did in UK and UAE, were exhibited in Sharjah. In the UAE, people were confused, and rightly so I would say because there was no art scene as the one we have now. People were not really aware like Hassan was of what any of these conceptual art schools were. There was a huge gap in the audience’s awareness and knowledge in arts, and what’s happening outside in the West. Hassan realized that and he started translating essays, short biographies of artists and writings on different schools of art. He translated them from English to Arabic and published them in newspapers so that people could be exposed to this material. Hassan had a column every week and he would critique the art scene as well. To have an art scene, you cannot just have artworks and artists and institutions. You also need to have an audience aware of what most of the art schools are, with proper art critiques. He realized that establishing this scene would take a long time to create, but someone had to begin doing it. If you collect all his essays that he published, you start to have a proper understanding of what ‘art’ is and a clear juxtaposition between Western art history and the local artists in the UAE that began producing. I know for myself it provided me good knowledge of who the key artists are and the movements.

As opposed to the UK, his works were well received. He had strong encouragement since he was at an art school. They were quite shocked of his works!

First Annual Emirates Fine Art Society Exhibition, 1981. Photo Courtesy of the EFAS, Sharjah.

MEA: Did he continue these performances at all after the early 1980s?

Mohamed: No that was it, he stopped in 1984. He felt he didn’t have anything more to add and he wanted to move on. It was during this same time he was also creating objects and he started to dedicate himself more to objects from that point.

MEA: How important was studying in London for Hassan? After London was there another country he traveled to that affected his art history practice as strongly?

Mohamed: It was a really turning point for him. There was no other country that he traveled to and affected his practice as much as London. In general, wherever he went, he was inspired by whatever he sees—in the banality of life and how people deal with their day-to-day. He actually didn’t travel internationally that much after London.

He would do many trips to the desert, and explore many places in the UAE. He was always discovering the areas around Dubai and Sharjah, particularly in the markets. He would find the material he used in producing his works there, all of these materials would come from so many different areas. In many ways his works trace some sort of geography or map.

MEA: Was there anything in his writings that he quoted on his performances?

Mohamed: I have to check on this, but I remember him writing about doing performances in nature and open spaces. Some of the points he had on this topic were that when an artist interacts with the desert, for example, he reconnects with nature and the artist uses that connection to create something of his own. The other point he had was that a place like the desert is often neglected. People might drive past it without stopping by to notice it. But when an artist puts something there, he makes people stop and wonder at that space to remind everyone that it exists. It is like giving that space a new memory. I am paraphrasing here, but I guess that’s what he meant.

MEA: How did Hassan archive and document these performance works? Did he paste all of the material on a sheet of paper as they are now displayed/exhibited?

Detail of Hassan Sharif, 'Swing,' 1983 66.3 x 48.7 cm Photographs mounted on cardboard Guggenheim, Abu Dhabi.

Mohamed: Either Hassan would take the pictures or his friends. Hassan would apply all of the sketches and photographs on the hard paper, he was doing all of the archiving at the time for his 1980s performances. With some of the performances done in the desert, he had his friends with him. One of them was my other uncle Hussain and they had taken the photos of Hassan. As for the photographs, for the performances that Hassan did in London, he used the dark room in his college to produce the photos, but I don’t believe that was the case in U.A.E. .

MEA: Did Hassan continue any dialogue throughout the rest of his life with any students/teachers once he moved back to the UAE?

Mohamed: After London Hassan was only in touch with one of his friends by email, his name was Andrew. Andrew would send an email and either myself or my dad would print the message and give it to my uncle who would read it, write his reply and this was how the conversations were exchanged.

In 2015 Hassan met his art teacher from Byam Shaw School of Art — Tam Giles at Whitechapel in London and she interviewed him there. They reconnected and they stayed in touch after that, it was very nice for both of them.

MEA: Do you feel Hassan worked most of the time in isolation?

In terms of work, he worked alone on most of this art. But he did not isolate himself. He did so towards his final years, but before that, specially from the 70s to late 2000, Hassan was outgoing, and he interacted with the art scene that took place in the area.

MEA: If Hassan were in the Quarantine today - do you feel it would affect his practice?

Mohamed: No one could think of what Hassan would be doing! But I am quite sure he would be producing works with masks and gloves. He actually already produced works with masks and gloves in the past. He would probably find some sort of irony of the quarantine that has indirectly affected the animals or some other beings and produce works reflecting this. He did something similar with a series of paintings on the economic crisis and he created his own irony out of it that. It would be quite interesting to know what he would be thinking of today to be honest..