This is an interview and exhibition review from "Place and Unity" exhibition held at Maraya Art Center, Sharjah, UAE.

31 October 2016 - 31 January 2017

This article was originally published in ArtAsiaPacific

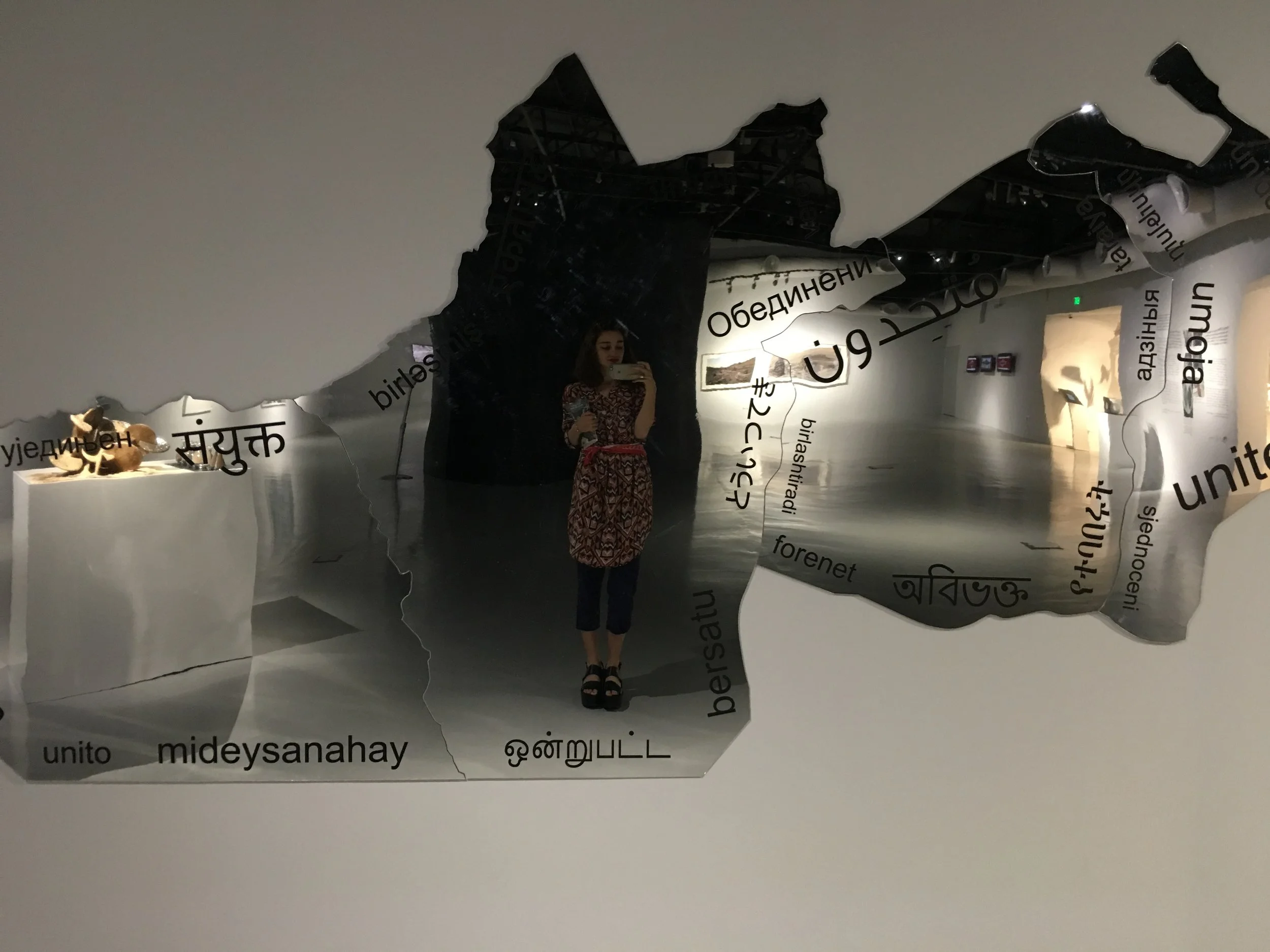

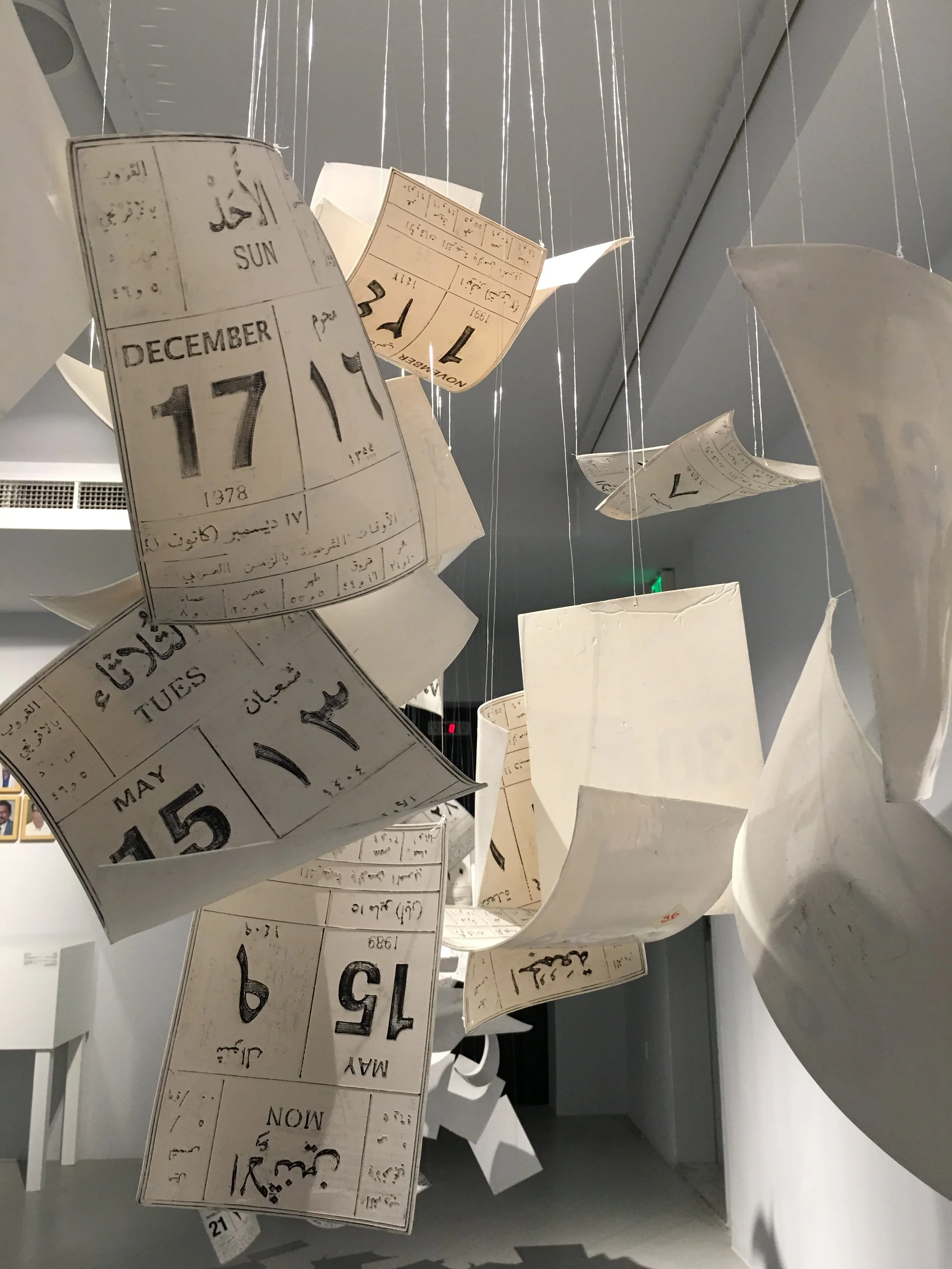

Maraya Art Centre’s latest exhibition “Place and Unity” explores the transformative role of the landscape in the United Arab Emirates, narrating both older and younger generation’s physical and emotional connection to the shifting sands and transient populations. Fourteen artists explore this notion of place, eager to preserve and archive these memories reflected on what the UAE space means to them, whether in the physical objects, in the architectural layout or by the interactions with travelers and residents. While many of the younger artists pay homage to the UAE in digital and graphic design, manipulating UAE maps or simulated installations, the featured older artists recount their memories through more traditional mediums and techniques, whether in paint and assemblages featuring found objects and film photographs. Embodying the cultural and spatial transformation that took place between the 1980s and ’90s, these older artists exhibit work with techniques that harken nostalgic memories of time and place while also maintaining a single thread of the UAE’s globalized and commercialized scene.

Portrait of Hassan Sharif. Photo by and courtesy Maaziar Sadr.Courtesy Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai, and Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

Khalil Abdul Wahid at his desk in Dubai Culture. Behind artwork by Musab Abul Qader Al Rais. Collection of Khalil's. 2011.

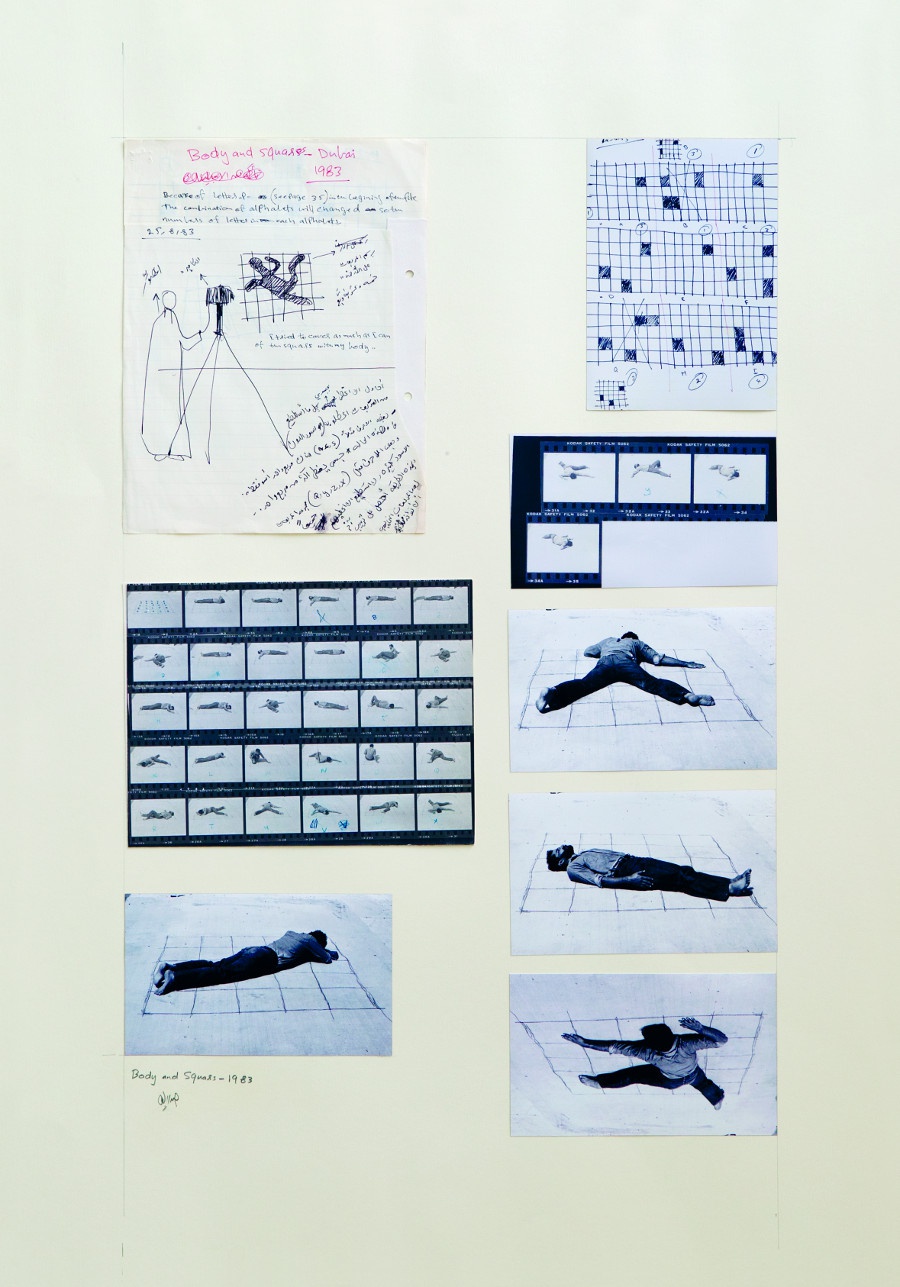

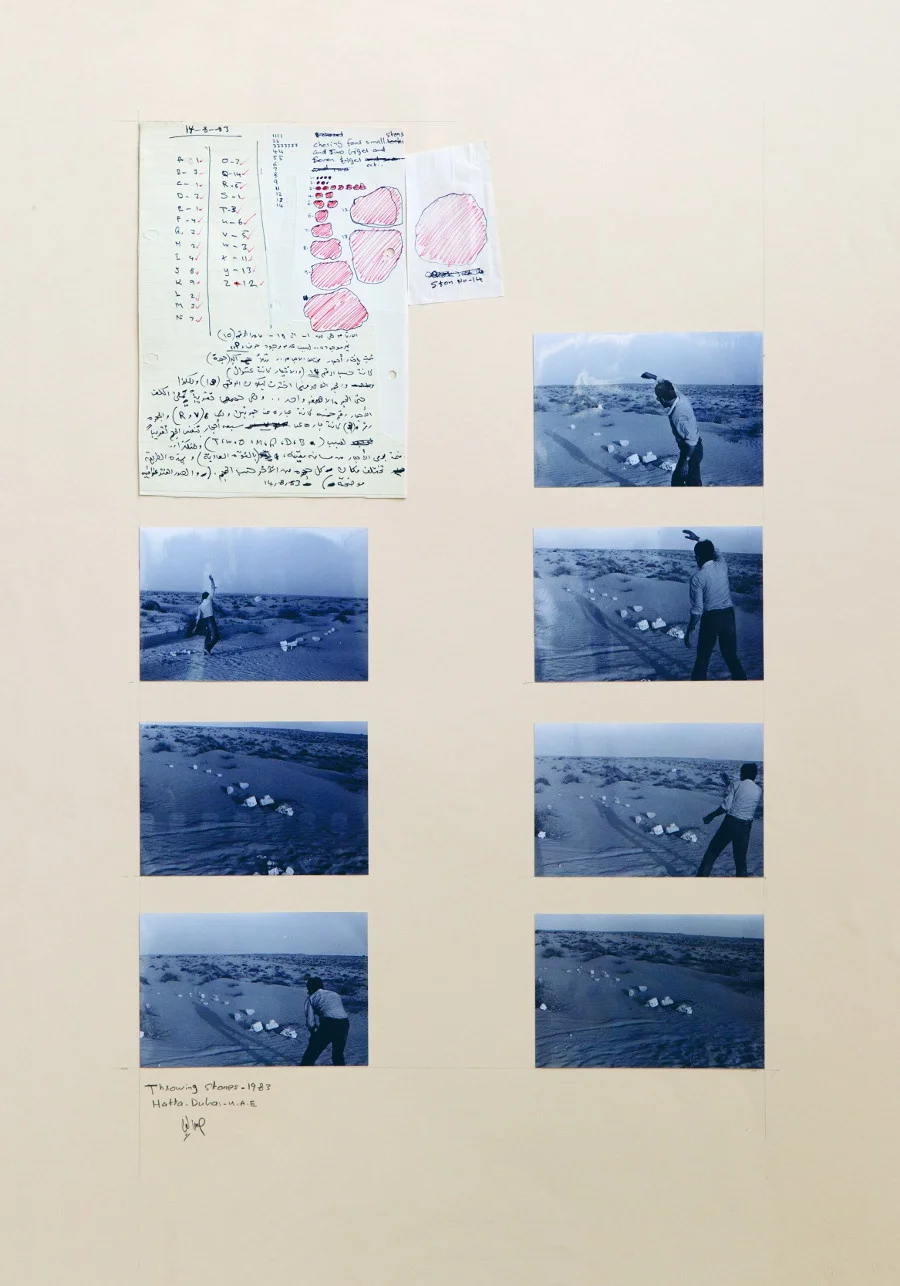

Connections in disciplines and training are woven throughout many of these exhibited works, one seen through the strong mentorship between the late Hassan Sharif (b.1951-2016), who passed away earlier this year, and Khalil Abdul Wahid (b.1974) . Both are artists from the older generation of Emiratis who have channeled their own experience growing up and practicing in the Emirates. Sharif is known as the grandfather of UAE contemporary art history, spearheading contemporary art discourse within the local community and facilitating dialogue across creative disciplines including poetry, as well as the visual and performative arts. Following his degree in London, Sharif documented and archived the most mundane activities and objects, filming himself jumping in deserts to displaying readymade objects within a community that was just beginning to appreciate conceptual art.

Hassan Sharif, Body and Squares, 1983.

Copyright the artist and Isabelle van den Eynde Gallery

Hassan Sharif, Throwing stones, 1983.

Copyright the artist, courtesy Isabelle van den Eynde Gallery, Dubai.

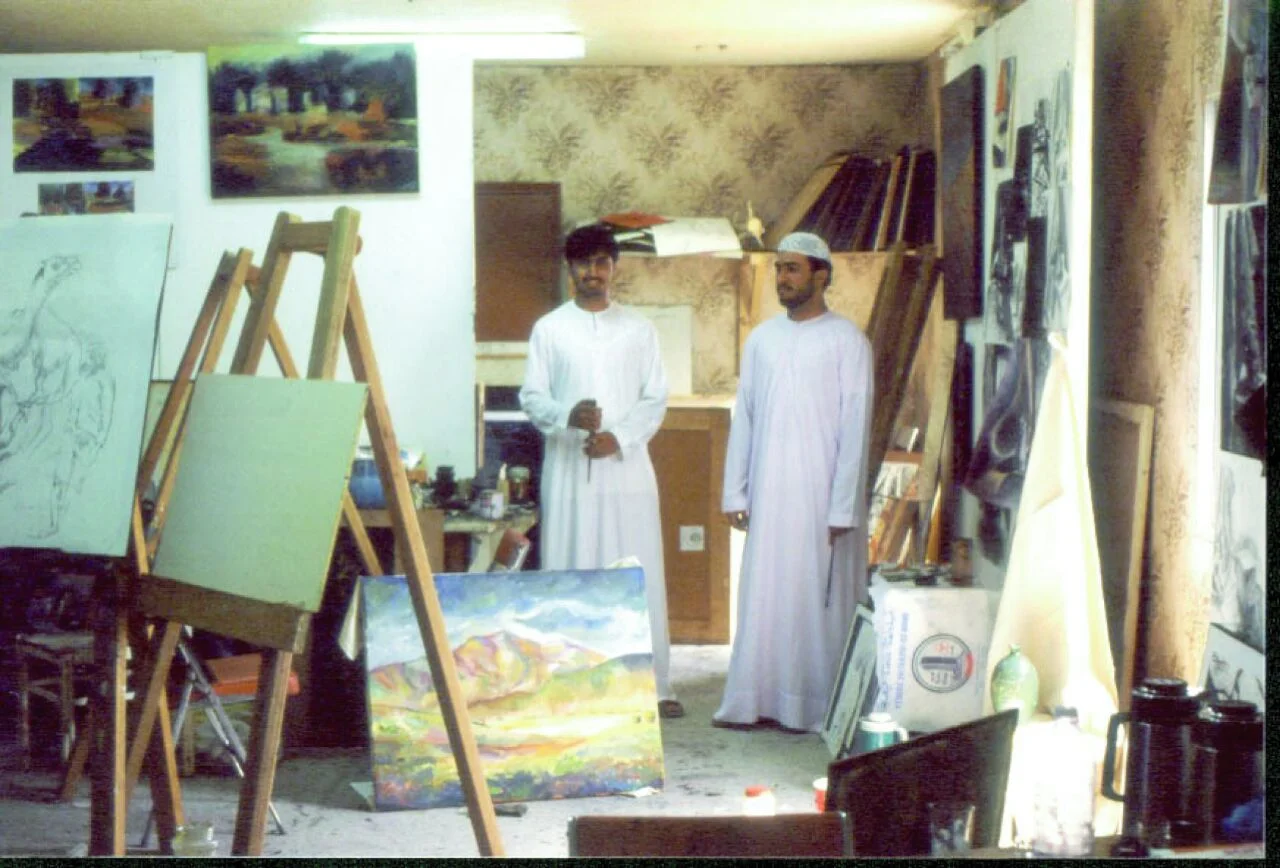

Khalil with his childhood friend, Mr. Saeed Mohammed Alnaseri in Marsam Al Hur in mid 1990s. Khalil is behind are his and another friend's paintings. Photo courtesy of Khalil Abdul Wahid.

Sharif mentored a group of artists in both Sharjah and Dubai, guiding them in basic art techniques and forcing students to experiment with the UAE landscape. Wahid was one of those students, trained in Marsam al-Hur, Sharif’s atelier in Dubai. Embodying the sweeping changes taking place within the spatial landscape as well as in the arts communities, most notably seen in the Emirates Fine Art Society in Sharjah, Wahid was part of a progressive and close-knit group that would incorporate Hassan’s practices within their own respective traditions.

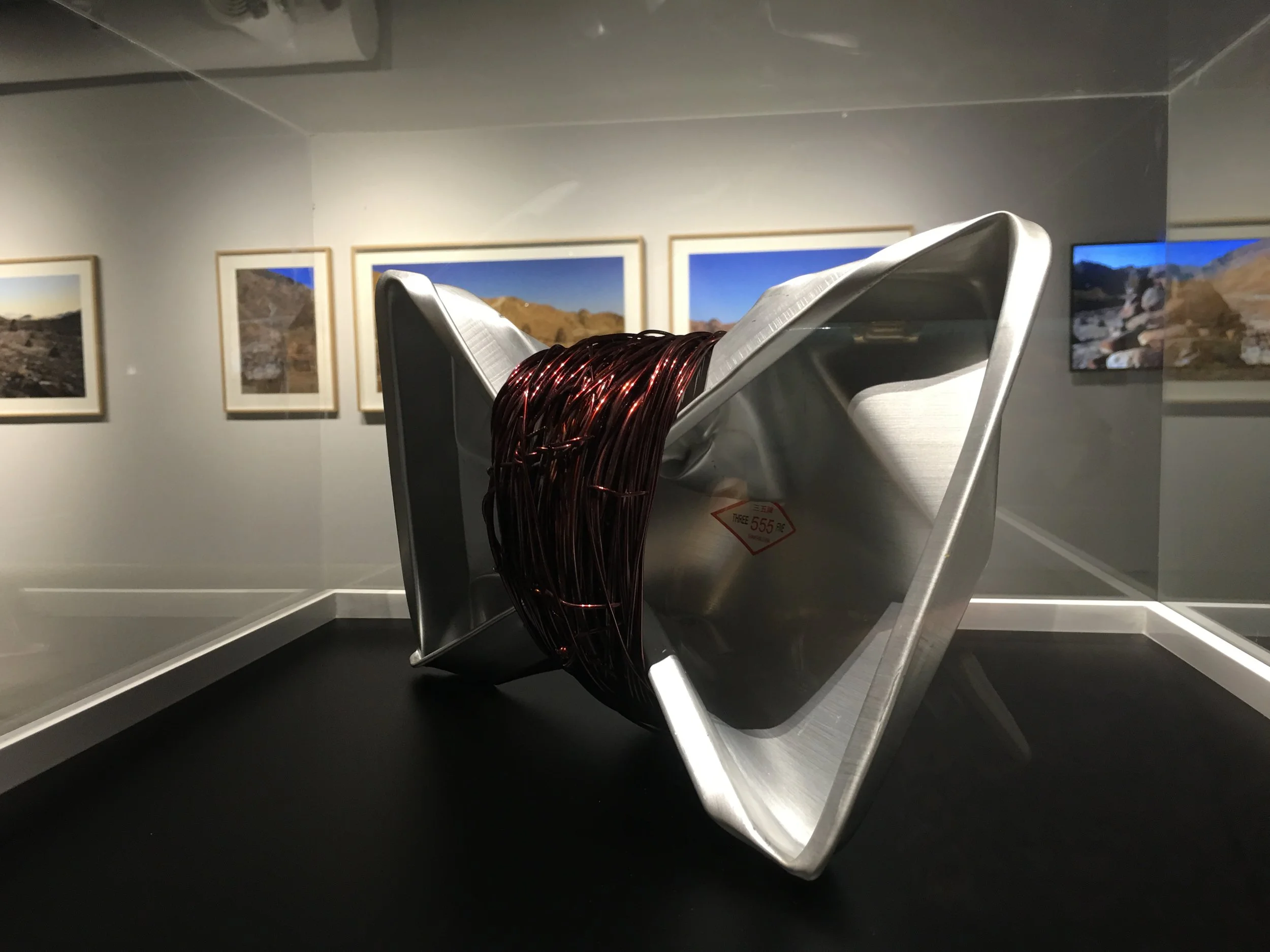

Although both artists’ exhibited works differ in medium and aesthetic, if seen within a wider evolution of contemporary art production in the UAE, Wahid has built on Hassan’s continued focus on archiving and communication with practicing artists today. This respective influence can be seen in their works presented in “Places and Unity”: Sharif’s Shanghai (2008), which features a warped tray constricted by copper wire, almost effortlessly displaying and bearing testament to the mass production and transfer of goods within today’s consumerist society; and Wahid’s “Artist Tools” series (2016), an assemblage of tools used by the several of the show’s participating artists, ranging from Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim’s muddy gloves used in the Khorfakkan desert to Hind Bin Demaithan’s Sadu textile fabrics and scissors used to make her digital postcards. By placing such emphasis in the artwork production, “Artist Tools” resurrects age-old traditions of documenting the creative process.

In December, I had the chance to sit down with Khalil Abdul Wahid in his office at Dubai Culture and Arts Authority, to which he has been manager of visual arts since 2008, as he reflected on his time as Hassan Sharif’s student and his perspective on the direction of the UAE art scene.

Can you tell us more about “Artist Tools”?

My latest practice is focused on the artist’s material. Each material has a story behind it. Most people don’t focus on it, but I thought why not see tomorrow from now? For example, if you look at Picasso’s tools, his stained, overused paintbrushes, who doesn’t want to keep his brushes after so many masterpieces were made from them? This idea lead me to think further on the activity of archiving, especially, why we think to document objects later, when everything is here now?

Khalil Abdul Wahid, Artist Tools, 2016 Photo Courtesy Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation

Khalil Abdul Wahid, Bait Al Shamsi Artist's, 2013. Exhibited at Emirates Fine Art Society exhibition. Photo courtesy of Khalil Abdul Wahid

What was your earliest education in art?

My teacher during secondary school was Iraqi artist Ihsan al-Khateeb. Khateeb noticed a few creative students and furthered our training and prepared us with rudimentary art skills. Since there weren’t any art classes in high school, the skills I learned from Khateeb prepared me well for my exposure to the Emirates Fine Art Society (EFAS) and training under Hassan Sharif after I graduated grade school. I consider myself lucky as most teachers in secondary school were not trained artists. Ihsan, however, was a practicing artist, and really took care of us, and even taught a small group of kids art lessons during recess. He made us participate in exhibitions within both our school and national exhibitions that involved all schools across the UAE.

Old Emirates Fine Art Society building near Old Safa roundabout. Photo courtesy of the Emirates Fine Art Society

Emirates Fine Arts Society, Sharjah, 1984. Originally published in Al Tashkeel 17 (2004). Courtesy of Emirates Fine Art Society

In 1989, Ihsan, a EFAS member, connected me and a group of young artists with Hassan Sharif. We were considered to be the youngest members of EFAS. I still remember in first year of high school when the principal gave us our membership letters into the EFAS.

Did you receive support from your family?

My dad loved to paint and draw and my older brother was very good in writing, with beautiful handwriting. I remember when my older brother was traveling, he brought back with him paint and a brush and I was so excited as a 13– or 14-year-old kid. I loved it so much and I didn’t want to even use it. I wanted to keep these tools forever! I never paid any attention to his early support, but realize now that it was a major inspiration for me to continue.

When did you meet Hassan Sharif?

Khalil and Hassan Sharif around 2000 at Bait Alserkal in Sharjah. Hassan was visiting the summer workshop taught by Khalil and Mohammed Kazem. Photo courtesy of Khalil Abdul Wahid

I met Hassan Sharif in late 1989 in Marsam al-Hur with another childhood friend. Marsam was an atelier in Deira near the old ministry building, which Hassan helped found in 1987. I began training with Hassan in 1990.

Can you share what is was like to study under Hassan Sharif?

Hassan started with basic fundamental techniques—painting drawing, and small sculptures, mostly focusing on still life. It was a step-by-step process, teaching us what was right or wrong, and making sure that when we did something wrong, we understood why. We practiced in pencil, charcoal, pastel, then oil color. I remember one time we had to crumble newspaper and mix it with glue, becoming a mud-hard object that had the appearance of dense, heavy concrete but physically featherlight. I wasn’t too keen on sculptures, but Hassan passed on to me that knowledge of how to create them. I eventually returned to painting, and even then, Hassan was teaching me correct fundamental painting and drawing, while allowing me freedom to explore the medium.

Can you speak about your practice? Is the concept of archiving an integral part of your work?

Khalil Abdul Wahid, The Mosque, photo courtsey Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation

Archiving is one angle. For me I was always focused on the object, especially in painting and drawing, it was good to know the technique and study the material used. Going back to Hassan’s newspaper sculptures, when you pick it up it’s just paper but when you look at it, it looks so heavy. I wanted to capture the physicality of the object used.

Apart from archiving, my work focuses on appreciation of the artwork and is developed through my relation with the artists. My end result doesn’t just connect people, but instead, always aims to link together a certain geographic area, or an event.

How was the studio Marsam al-Hur different than EFAS?

EFAS began in 1980 and was founded by group of artists such as Hassan Sharif, Ahmed al- Ansari and Dr. Mohamed Yousif. It was seen as a place for artists and also writers and musicians to get together and have exhibitions that fostered an understanding of the artwork and its concepts. Marsam al-Hur was an atelier, opened to youth between the ages of 15 to 35, mostly from Dubai. While the EFAS was a base that featured exhibition, both at the society and in spaces throughout the UAE, Marsam was more of a workspace for arts training.

What would you say about the future of art development in the UAE in terms of art criticism?

The UAE needs more people who involve themselves in literature to understand that art form. I know in the 1980s and 1990s people from poetry, film and music circles were offering art critiques in newspapers and journals. Even if one is not involved in visual art, there is always something for writers from other disciplines to discuss visually or conceptually. This increases knowledge, discussion and awareness.

As for my hometown, I do have a really positive and strong feeling of the developments happening in Dubai. Growing up in the city I was always accustomed to the fast paced, and rapid changes in both ideas and urban structures, and I had to train my mind in a way to adapt to these changes surrounding me as I myself was growing as an artist. I feel Dubai will have a strong base in fostering these art discussions, especially in government organizations. The speed of these developments is parallel with the rhythm of the city.

Do you think growing up and living in Dubai, you’re used to this destruction and renewal since the landscape seems to change every year?

I am extremely interested in exploring the transformative nature of Dubai. In terms of history, if you talk about the “old,” how old is it? I look at this change over time in terms of objects and how they exist within our environment. What you used to have starts to become old because it’s because it’s no longer in vogue, not because its actually old! At the same time it will not disappear. A lot of people are not paying attention to this concept. Now the object is available; but after 10, 20 30 years, it will not exist in the same way it had been existing within the place. Bringing it back to my artwork “Artist Tools,” I want to bring artists together to reflect on the idea that we are part of the movement.

Would you like to bridge these urban developments to your own artistic style?

Yes, as “Artist Tools” preserves these artists’ materials, I want to touch upon the preservation projects across the old Dubai covering the Fahidi ara and Old Souq because they are taking part in preserving the oldest layers of the housing projects. Now with the new urban planning developments, they are using modern material in cement and concrete to replicate the old houses made of stone. It is important for me to document these disappearing older places by displaying them in my work and contextualizing these materials as part of the history of UAE architecture.

Who do you feel is the closest to following Hassan Sharif’s legacy of mentoring?

Hassan was ahead of his time, and I believe the people that studied directly under or with him will be able to pass down Sharif’s knowledge to future generations. Sharif was associated with “Al Khamsa” a band of five artists including himself, his brother Hussain Sharif, Mohammed Kazem, Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim and Abdullah al-Saadi.

Left to right - Mohammed Kazem,Bert Herman, Khalil Abdul Wahid. Around 2003. Photo courtesy of Khalil Abdul Wahid

More specifically, I am confident in Mohammed Kazem, both as my friend and because he was one of the only few students trained under Hassan who was able to get very close to him. After joining the Emirates Fine Art Society at age 15, training directly under Hassan, Kazem eventually assisted Sharif in his studio workshops in Dubai and Sharjah. Kazem has an open hear like Hassan’s. Both are great artists, and both know how to seek those with a passion for art and how pass on that knowledge.