UNRAVELING TIME-WARPED THOUGHTS..

Salvador Dali, ‘The Persistence of Memory’ 1931, oil on canvas. © 2020 Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dalí

Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

It has been nearly one month of letting the pressure cooker of isolated thoughts and existence churn and compress internally during my new quarantine life.

A menagerie of wishful thinking and troubled internal grievances are swallowed down by an abundance of too many cups of homemade Turkish coffee and an oversupply of Zoom conference calls.

Just as our grievances are indefinitely felt collectively—by our neighbors who share our streets or apartment floors, along with the pixelated faces we see on the internet, each one of us can attest to a unique quarantine life that is quintessentially ‘ours.'

It’s as if we should place yellow tape outside of our ‘habitat’ labeled ‘UNDER CONSTRUCTION UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE’ to ward our family and friends along with our social media community as we plead ‘Forgive me in advance, for I am ‘quarantine-ing!'

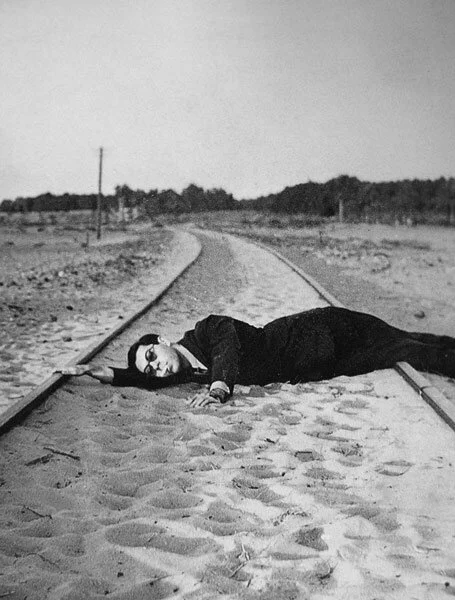

Abduh Khalil, Untitled c 1949. Photograph: Tate Liverpoo

We are neither here nor there, we are plagued by an in-between absentmindedness, lapsing in a state of timelessness without peripheral boundaries. We are unsure of where and to what extent do thresholds exist anymore.

Just last month during Art Dubai’s Global Art Forum’s live webinar stream, commissioner Shumon Basar shed light of the situation “It is clear that the future has been canceled or at least indefinitely postponed. All this un-futuring makes the present feel strange and unique. As Canadian artist and novelist Douglas Coupland has suggested ‘the present and the future are now the same thing.’ “ (Aired live on 25 March 2020)

In my current quarantine life, one of the worst feelings I have felt is the yearning to extend myself out of my sheltered space, to exist within the public realm again and physically identify as a community.

As I write this, it’s hard to remember my last conversation to a person in flesh - it all sort of jumbles into a scrambled eggs’ worth of mismatched, pixelated visuals.

And as we yearn, we reach our hands to grasp the faint, unattainable Rothko-esque horizon line we see out of our balconies, our bedroom windows and in the perimeter of our computer screens.

We then realize our arms’ and eyes’ extension is rooted in reality, from a single chair, some more comfier than others (mine slightly resembles Mona Hatoum’s below), that has come to know and hold us more than anyone else at this point.

Mona Hatoum, 'Remains (chair), 2017, wire mesh and wood. Image courtesy of White Cube.

The notion of 'in-between-ness’ as raised by Fatima Albduoor in an interview with her earlier last month actually triggered an earlier relationship with this sense of being not only felt in my life, but also readily apparent in my interviews with many artists and creatives.

'I never said it would be easy, I only said it would be worth it.’ -Mae West

Georges Henein (1914-1973). Photography by Boula Henein

Over the course of these few years I have acknowledged the multiple layers of impermanence and transience in fulfilling any social and vocational obligations in my life; whether expected upon me by my superiors or involuntarily acted upon in search for personal growth.

While in-the-moment, these transformations were never easy, whether they be slight or monumental, my mind in many ways subliminally resisted these maneuvers and changes as I trained myself to ‘untrain’ the habits I have come to live with.

Despite the challenges, we all have experienced this and transformed —for better or for worse, into an altered version of our previous selves and lived to be the judge if it were to our liking.

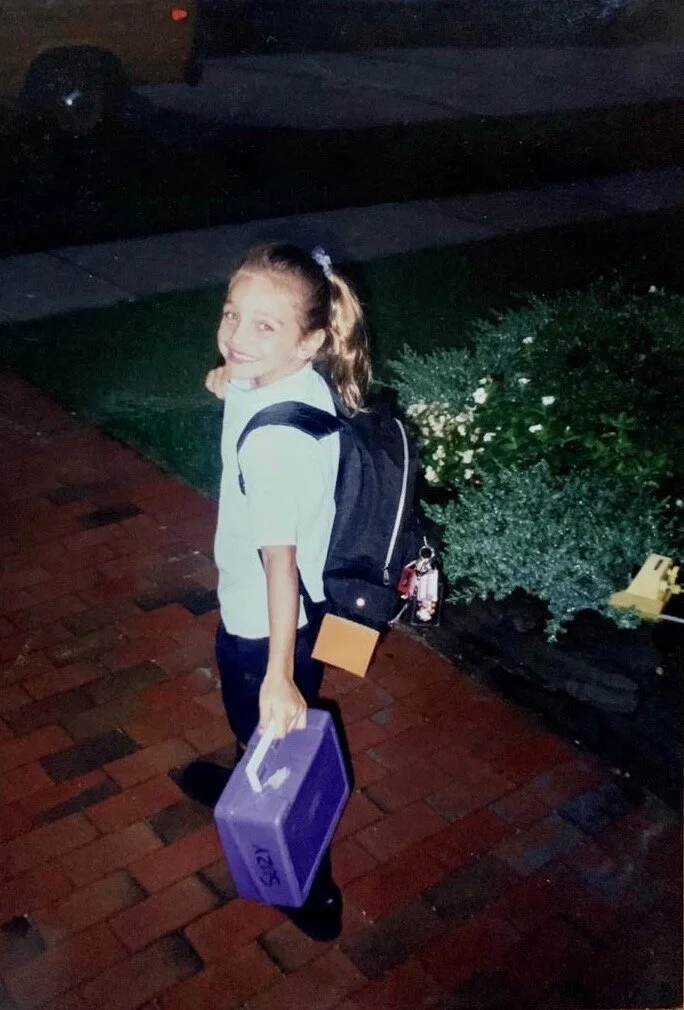

Suzy on her normal 6:15am pickup on her way to school. Circa early 2000s. Image courtesy of Suzy Sikorski.

A GLOBAL BALACING ACT

I am an American girl from a small beach town in New York who has merged and adapted to a new and ever-evolving life halfway across the world in Dubai. I have come to feel ‘suspended and betwixt between two cultures.’ My passions as an art researcher is anchored deep within the desert sands of the UAE, and every part of me falls within the crevices of these artist’s life stories and holds fast to their studio spaces. Just as I advance in my research, I have maintained roots within the seashores of Long Island, NY. This sensation is heightened now more than ever as I type from my apartment bubble high in the sky. (1)

But this notion of ‘suspension’ had unraveled itself earlier than I’d thought.

Since age 6, I traveled nearly 45 minutes each-way to attend private school everyday, with very a disparate social life located in separate and far-off places across Long Island. Shuttled between school, soccer and flute practice. Consequently, much of my development was nurtured just as importantly in the vehicle that brought me to these places —my small yellow school bus (you can actually see the bus in the picture of me on my early bird commute!).

My incredibly long bus rides to school were the first distance away from my parents, and we all lived to tell the story. We survived as every kid does, coming to terms with how to live without their constant supervision.

En route to my school, I experienced these mornings by myself, with a cinema front seat view of a golden suburbia filled with white picket fences, freshly groomed dogs saying goodbye to their owners and the sweet scent of Eggo waffles lingering - a true American staple for children. They were without an iPhone or iPod, except if I was lucky and charged the batteries-- either my Gameboy or a Sony CD player with the latest ’Now That’s What I Call Music' album.

Some days would go quicker than others; I would play mind games with myself as I sat and looked outside with the other children who were too tired to speak at 6:15am, in anticipation (some more eager than others) for the bus to take us to school. But I grew creatively because of this, training my mind to experience my surroundings in an alternative and contemplative way.

Almost 20 years later, and made readily apparent during this quarantine period, I find myself again on this yellow magic school bus.

But more like NYC’s 42nd street Grand Central terminal shuttle transporting me everyday from the USA, UAE and all that lies ‘in-between.'

Just as I carry with me a lunchbox (to see the stylish purple one I am holding) full of freshly packed daily conversations with family back home, I am organizing the treasure trove of archives I’ve documented with Emirati artists and working steadfast in building a strong October sale for our Christie’s team. I rustle the lunchbox a bit more and find at the end of my Cracker Jack snack box are a treasure trove of déjà vu moments as a child that seem to unfold the more the quarantine life has set in (Note: American children loved opening Cracker Jack boxes to find the paper wrapped toy prizes hidden within these caramelized snacks).

I am without a definitive answer when this self-isolating ride will be over and what the final destination will be post quarantined - and it sure isn’t 2nd grade class, period 1.

The only realities are my awareness of what is happening now and ultimately once this isolation period is over, a measurable understanding of the transformations that have taken shape in me.

So for now, I am surrounded by a menagerie of an endless supply of unread books and scattered post-it notes containing scribbles of unrealized projects to complete both in isolation and then once I’m liberated from this quarantine. Along with a sweet supply of American films to add to my blockbuster list that have made me feel I’m in a complete time-warped vacuum. Until further notice I am pretending to have my morning coffee in Charles Foster Kane’s mansion Xanadu (‘Citizen Kane’ - 1941) and rummaging through old memories in the basement with Brick in ‘Cat on a Hot Tin Roof’ (1958).

Ayman Yossri, Daydban, ‘Maharem’ 2009, silk screen prints on 64 wooden tissue boxes. Christie’s Images Ltd.

UAE UNLIMITED’S ‘BAYN’ EXHIBITION

My isolated evenings have allowed me time to reflect on some of the key exhibitions in the UAE that have shaped the way I approach art historical analysis and alternative methods of art production. In 2017 while on my Fulbright scholarship grant, I attended UAE Unlimited’s third edition of an exhibition titled ‘Bayn’ (in Arabic meaning ‘between’). UAE Unlimited is a satellite platform established in 2015 for young artists in the UAE that is founded and supported by His Highness Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan bin Khalifa Al Nahyan and managed by Executive Director and Art Adviser, Shobha Pia Shamdsani. Collaborating with institutions including Warehouse 421, Alserkal Avenue, Maraya Art Centre and most recently NYU Abu Dhabi, UAE Unlimited allows these young artists the chance to work with a dynamic curator and senior advisors from across the country.

‘Bayn’ was curated by Munira Al Sayegh with assistance from senior advisor Maya Allison and included eight emerging artists and one eminent guest artist centered around this theme of ‘in-between-ness,’ articulating a sense of perpetual transformation on multiple levels. Experimenting with a mixed array of material including sound installations, marine calcified rocks and plaster casts of the mountains in Ras Al Khaimah, artists tackled different notions of liminality within the physical/ external realm while also in the personal one. The exhibiting artists included Asma Alahmed, Hatem Hatem, Manal AlDowayan (as guest artist), Maytha Al Shamsi, Nasser Alzayani, Saif Mhaisen, Sara Al Haddad, Talal Al Ansari and Talin Hazbar.

Talin Hazbar, ‘Accumulation’, 2016-17, Gargour, accumulation. Image courtesy of UAE Unlimited and the artist.

Accompanied by the show was a reading session opened to the public and moderated by Munira that I had the pleasure of attending. It was during this event that I learned of the term ‘liminality’ - derived from the 17th century Latin word ‘limen’ meaning ‘threshold’. First introduced in 1909 by ethnographer Arnold van Gennep in his book Les rites de passage, the notion was observed within certain social obligations such as coming-of-age rituals like marriage, childbirth and even crossing borders to a culturally different territory. He denoted completion of these rites by a three-part sequence:

1. Separation

2. Liminal Period

3. Reassimilation

It was later in the 1960s when the text was elaborated by anthropologist Victor Turner who emphasized the second tricky term, that of the liminal period, describing this ‘subject of passage ritual is, in the liminal period, structurally, if not physically, invisible.’ (2) It is for us a midpoint between the starting and end point that is a temporary state ending when we are again reincorporated with society. It is a state where we accept of who we were, but also what we are now and eventually becoming. Ultimately from the themes proposed, we ultimately are only to make sense and identify with this evanescent sensation the more we experience the trials and tribulations of life.

The Middle East has witnessed an enormous sense of transformation that has affected all aspects of life, from shifting borders, to political upheavals and spatial reconstruction and modernization. The UAE in particular, founded in 1971, has witnessed tremendous and unparalleled change and growth reflective across all generations who have lived here. Just as the landscape changed, so did the implications in the social and cultural spheres. As Munira states in her intro essay in the ‘Bayn’ catalogue ‘The single lensed history of the romanticized recent past and the finalized putative vision of the future highlights a gap in the importance and the understanding of the present in-between moment of the UAE’ (3).

The thematics of the ‘Bayn’ exhibition and programming stimulated the inner ‘in-between-er’ felt in me that has lingered in my thoughts and conversations since then. It was the first time I acknowledged this sensation individually but also inter-connectively. Each visitor and exhibiting artist articulated differently these observations and internal sensations, as reflective within artist Sara Haddad who later that year exhibited at the Venice Biennale 2017:

‘The theme of the exhibition was very relevant to me at that time. I had just returned from Baltimore after completing my MFA and was still navigating through my surroundings. Emotionally I was still very connected to Baltimore and the relationships formed there, and had a difficult time being present in Dubai. What I really appreciated with Bayn/U.A.E. Unlimited, is that I was given the opportunity to explore themes of my practice through the use of unconventional mediums, including lashes and impressions on tissue paper. I was able to unpack figuratively and literally; these were objects I brought back with me that were representative of times, places and people. I had an emotional connection to them: they took me back to a memory. Once the objects held a new space at the exhibition, new emotions were formed thus new memories, which I experienced every time I re-visited the space.’ (the artist in conversation with Suzy)

I had the chance to interview the curator Munira Al Sayegh on her notions of the themes of this show and the overarching implications this '‘in-between-ness’ has cast on our new quarantine lives these days.

Our conversations in our interview below trail from her personal life— in her love for her dogs, growing up within an ‘80s baby’s generation’ in the UAE, along with her takeaway moments of the first show she ever curated.

Side note: last time I attended one of Munira’s events was during a late night meditation during Ramadan for artist Shaikha Al Ketbi’s installation in Warehouse 421— confirming she is just as awesome as a curator as she is on the yoga mat!

Image courtesy of Munira Al Sayegh.

MEA: Can you discuss further how you came up with the ‘Bayn’ theme for the exhibition?

MAS: The feeling of ‘in-between-ness’ was something I felt for a very long time. Notably as coming from a generation that exists between my parents' generation that grew up during the oil boom and the unification of the UAE, and then the next generation who will grow up with all of the creations of the hard work that took place in the last 20 year by people who exist in my age group. We’re what you call ‘the ‘80s babies.’ For us in the UAE there is this general constant notion of looking forward, and looking at the future as fact, but then never focusing on the current. In order for the future to come to actualise, it is the present that needs to take place correctly. That current state exists in the hands of people for our generation.

MEA: How were these in-between notions personally felt in your upbringing?

The state of ‘in between’ is something I have always existed in during my upbringing in Abu Dhabi. I went to an American Community School which needed to keep a 99% rate of American students. I always grew up with American friends who lived very different lives and cultures than me. The school was always that sort of bridge that connected various cultures to one another. But I always existed in this middle point - I was neither one nor the other. That is something that began to inform my thinking for this exhibition. It is the reality of my life and so many others just like me.

Manal AlDowayan, 'Tree of Guardians,' 2014. Brass leaves, ink and fishwire. Image courtesy of the artist, Sabrina Amrani Gallery and UAE Unlimited.

MEA: Do notions of ‘in-between' still exist for you today in COVID times?

MAS: The notion of in-between always exists, especially now more than any other time. I think if you had asked me this question outside of COVID times, I would’ve said that I really don’t feel that sense of liminality where I am in-between thoughts or physical spaces and mental. What is interesting though is that right now with the situation that we are in and the virus that has taken over, there is no in-between or liminality, unless you live to attempt to gain clarity for the future. But if you are in the here and now - you are stuck in a ‘purgatory’ more than liminality! It is a sense of existing in one place and actively acknowledging how we are existing in that one place. It strips us away from time and I think that is a very interesting feeling to be in, where weeks and days melt into one another. The only thing that dictates fact is yourself. You find yourself away from this defined state of time or defined notion of a future because nothing is defined.

Sara Al Haddad, ‘I am overwhelming’ 2016-17, mixed media. Image courtesy of the artist.

MEA: How successful were the artist reading groups for you? (note to reader: Munira held monthly reading groups with the artists in preparations for the show and then opened this up to the public)

MAS: The reading groups for me were one of the most successful activities that took place during this time. I was very grateful to activate this with the artists and to have personally learned and benefited so much from these sessions. In general, reading is such a personal mind frame and state where you are alone in a room or quiet space and you read with regards to you in your own voice. You never read out loud to one another. It is something we normally assume is set for children and once you’re an adult - you can’t do that anymore. The public reading group that you had attended I found to be extremely interesting and enjoyable as it started to bring different voices into the same text. It is very important for texts to be discussed in order for you to actually understand it.

MEA: Did you feel any particular artists had personal breakthroughs participating in this exhibition?

MAS: I think all of the artists had a particular breakthrough one way or another through this exhibition from my own understanding. One in particular who transformed the most was Maytha Shamsi who is a writer and musician who had experimented with sound art. I am grateful to have her and her work come to life through this exhibition.

(Note to reader: Maytha displayed sound pieces that showcased what a sonified mind would sound like (‘The Curator’), along with a series of sounds inspired by the two main bridges in Abu Dhabi (‘Bayn Jisrain ‘Between Two Bridges’), and a soundscape of natural and electronic sounds heard in Abu Dhabi, such as the car horns, the movement of the water in the seas, and the echoes of various languages spoken (‘I am Hear’). )

MEA: All works fell under the categories of physical or external shifts or personal nuances. Did either of the two categories resonate more with you at the time?

MAS: I think of course personal shifts are what make me who I am and acknowledging these shifts is something that I have to practice regularly and daily with myself. In one way or the other, you are always in a liminal state, always in a state of becoming and trying to arrive to the better version of who you want to be. I am very self aware and self critical of my needs; they are always shifting because I really know how to study myself and my wants and how to arrive to what my needs are. The personal notion of liminality is interesting to me. Although all the artists spoke between the physical and the personal, you cannot separate the two on the micro level as they are one and the same. The reason why the physical becomes important is because it impacts the personal, i.e the self, and you cannot separate the two as they are very much interlinked.

MEA: What were some of the most emotional and poignant works for you in the exhibition?

MAS: Three works that really spoke to me attest to my mental and emotional state at that time and are as follows:

Sara Al Haddad, ‘romanticising yesterday’s’ 2016-17. Cork bottles, eye lashes. Image courtesy of the artist.

Sara Al Haddad’s work collected physical parts of her being and her surroundings and it created this sense and notion of picking yourself up and discussing this idea of the in-between with the self that is trying to respond to location, space and place. Her works had titles such as ‘Inhale,’ ‘I am sorry,'‘ ‘I am overwhelming’ and ‘exhale’ think that is something we all kind of go through. Sara at that time just came back from her Masters in Baltimore, Maryland and was existing in this sort of shift in landscape that I even can attest to personally once returning from my studies. This feeling pushes us to a new limit in order to get to know ourselves better.

(Note to reader: Sara displayed objects she had in her studio in Baltimore, stitched tissue paper, collected eyelashes, and a box casted identically to one she used to move from Baltimore to Dubai)

Talin Hazbar looked at the gargour, the traditional Emirati fishing net and explored how the sea adopts the gargour and makes it a part of the landscape and environment. The work is extremely poetic and important to discuss because Talin’s being, negotiates this same sense of someone acclimatizing fully to a new environment and place as a Syrian growing up in the UAE. The connection to this work took me back to when I was in school and my best friends at the time were Palestinian/Iraqi and American. They always considered Abu Dhabi and the UAE their home. I don’t see a separation with any of them to myself. I consider people who are born and bred in the UAE an equal part to the ecosystem as I am, as someone who is Emirati. This is the case of Talin’s work, she brought to life this sensation that is felt by many through objects that translated poetically.

Saif Mhaisen’s work is another one that struck me – a life-sized photograph of Saif in two separate human beings although they are the same human. The work showed Saif a year and six months apart, beginning in 2015 and ending in 2016. The liminal becomes a question and the transformation becomes the framework that is highlighted.

Saif Mhaisen, 'Self Portrait 11 & 12', 2015-2016. Digital photography, print on canvas. Image courtesy of UAE Unlimited and the artist.

MEA: What was the most challenging part of curating Bayn for you?

MAS: It was my first exhibition so the most challenging at the time was knowing how to navigate critique and how to push an artist to satisfy their fullest potential.

MEA: We have been discussing all that is ‘in between’ - but what is a constant in your life?

MAS: A constant in my life has been surrounding myself with art since when I was a child, along with appreciating nature and my pets. I really fall back on the arts for many reasons and find it to be a continuous attachment. I feel a sense of liberty within this field and of the community we are a part of. That liberty allows me to always push and question things whereas in other fields you have more constraints with the framework that is set forward. I used to be a painter and initially wanted to go into art practice and slowly that practice after university died down and my writing practice picked up. I have been writing since a very young age and that to me is a constant I cannot live without.

MEA: What is the most special place in the UAE for you?

MAS: Bahrani Island which is about 20 minutes off the coast of Abu Dhabi. We used to go all the time as kids with my uncle. We would take the boat from Abu Dhabi’s coast and we’d spend the full day on the island there running around and playing on the beach. Later when we grew up as teenagers we used to take the boat out on our own and it continued into my adulthood.

MEA: Favorite artist and artwork recently?

MAS: Favorite artist and artwork is Hashel Al Lamki who I had the privilege to work with for two years and together we worked on his first major solo show ‘The Cup and The Saucer’ that is up at Warehouse 421 right now. My favorite artwork is The Volcano Fountain a stained glass work that is reminiscent of the Abu Dhabi’s volcano fountain on the corniche.

Hashel Al Lamki, ‘The Volcano Fountain.’ Image courtesy of the artist.

MEA: One of the most important shows that stuck with you these past few years?

MAS: One of the most important shows I’ve seen recently was in 2017 at the Barbican in London—”Basquiat: Boom For Real.” It really shifted a lot for me in my curatorial and creative practice. I didn’t expect the show to impact me so personally. In a way the show really focused on the state of being for artists during Basquiat’s time in New York and this interconnectivity between artists, writers and singers. There was this real sort of push that was taking place on the ground very organically and then the museums and the galleries began to respond to them at a later stage. For me that is extremely fascinating because I feel that is a state that we are currently in regionally. There needs to be more of an organic scene here that helps equalize the spectrum of the arts ecosystem. This is exactly what my practice is - shifting the narrative from institutional thinking to more community based efforts.

Saif Mhaisen, Detail of ‘Self Portrait 11 & 12', 2015-2016. Digital photography, print on canvas. Image courtesy of UAE Unlimited and the artist.

At this point I feel all of us will have our own version of Saif Mhaisen’s work ‘Self Portraits 11 & 12’ depicting ourselves pre and post quarantine. The work showcases the artist at two very different stages of his life, at one year and six months apart beginning in 2015 and ending in 2016. We see a transformed Saif within a very clinical white space and devoid time and space. On the left his gestures are very stern, certain and definitive, while on the right we see a clean-shaved man listening to his counterpart. Today knee-deep in this quarantine madness I am still trying to formulate my own sense of ‘Self Portrait II’ amidst a total delusion of time and place, but aware of powerful changes taking place within me.

Until then— happy quarantine-ing everyone!

Bibliography:

La Share, Charles, “What is Liminality?” 18 October, 2005. http://www.liminality.org/about/whatisliminality/

Turner, Victor, “The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual” (1967). (p. 95)

Ex. catalogue, Bayn, UAE Unlimited, Maraya Productions, 2017, UAE (p.28)